Philadelphia Criminal Defense Blog

Did an Assistant City Solicitor Commit a Crime When He Photographed His Friend Tagging a Fresh Grocer with Anti-Trump Graffiti?

If you’re hanging out with a buddy and your friend does something illegal while you’re there, are you on the hook for the crime? What if you knew or suspected that he was going to do it? Those are the questions likely facing Philadelphia prosecutors as they decide whether to bring charges in a case involving an Assistant City Solicitor who, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, was videotaped “involved in an anti-Donald Trump vandalism incident.”

The video, which is available on the Inquirer’s website, shows the man “wearing a blue blazer and holding a glass of wine, filming or taking photos, while a second man spray paints ‘F--- Trump,’ on the wall of a newly opened Fresh Grocer.” That certainly isn’t good behavior for a city attorney. But given that he wasn’t the one with the spray paint, did he commit a crime by watching and taking photos? The answer to that question starts with an analysis of Conspiracy law. In other words, the question is whether the video provides the Commonwealth with enough evidence to bring a conspiracy charge.

Most people have a general idea of what a conspiracy is, and on its face, it looks simple. Conspiracy is an agreement between two or more people to commit a crime. Conspiracy punishes not just the commission of the crime, but also the fact that the conspirators made the illegal agreement. Conspiracy is illegal because legislators have generally decided that people who plan crimes in advance with other people should be punished more harshly than people acting alone or who commit crimes impulsively. For this reason, conspiracy is a separate offense from the crime which the parties agreed to commit. Although conspiracy seems like a simple concept, in court, it is more complicated than it seems and can be very difficult for the prosecution to prove. The Pennsylvania Crimes Code defines conspiracy as follows:

A person is guilty of conspiracy with another person or persons to commit a crime if with the intent of promoting or facilitating its commission he:

(1) agrees with such other person or persons that they or one or more of them will engage in conduct which constitutes such crime or an attempt or solicitation to commit such crime; or

(2) agrees to aid such other person or persons in the planning or commission of such crime or of an attempt or solicitation to commit such crime.

In plain English, this means that a person commits a conspiracy when they agree to commit or try to commit a crime or when one person agrees to help the other person with planning or committing a crime. Additionally, the prosecution must show more than just the existence of an agreement. The Commonwealth also must show that one of the conspirators committed an overt act. The overt act requirement provides that “[n]o person may be convicted of conspiracy to commit a crime unless an overt act in pursuance of such conspiracy is alleged and proved to have been done by him or by a person with whom he conspired.”

The overt act requirement ensures that people are criminally liable only when they take real steps towards committing the crime. It protects people who talk or joke about committing a crime but do not really mean it. For example, if you and I enter into an agreement to rob a bank, we have not committed a crime until one of us actually does something in furtherance of the agreement. However, it is important to remember that we do not both have to do something in furtherance of the conspiracy. If we make an agreement and one of us does something substantial in furtherance of the conspiracy, we have committed a crime. If we agree to rob the bank and you go buy the masks, we are now both on the hook for conspiracy even if I did not actually do anything other than agree with you that we would rob the bank.

Conspiracy is a complicated and often difficult charge to prove because most of the time, unless they have a wiretap, cooperating witness, or undercover officer, the prosecution does not have evidence of the actual agreement. Instead, the prosecutor will produce testimony or other evidence describing the actions of both defendants during the incident and ask the judge or jury to infer that the defendants must have agreed to commit the crime together in advance. This is where the difficult questions arise; when one person commits the crime with another person present who does not do anything illegal, are they both on the hook? Without concrete evidence of a prior agreement, the answer is often no.

The answer is often no because Pennsylvania law provides two important defenses to conspiracy: “Mere Presence” and “Mere Participation.” The mere presence doctrine establishes that the defendant’s presence at the scene of the crime or in the company of whoever committed the crime is insufficient to show participation in a conspiracy. This is true even where the defendant knew or suspected that the other person intended or planned to commit an unlawful act.

For example, if you and I are walking down the street, and I punch someone in the face while you stand there, the evidence would be insufficient to establish that there was a conspiracy because there was no evidence that you agreed to or encouraged the assault in some way. Although running from the police is almost never a good idea, this is true even if we both run when the police show up to make an arrest. Mere presence means that the prosecution must show that the defendant was part of the agreement, not just that he was there or that he knew about it.

Mere participation is another important defense to a conspiracy charge. Mere participation is the idea that when a fight breaks out involving multiple people, the spontaneous eruption of the fight is not enough to show a conspiracy charge. Pennsylvania appellate courts have recognized that “the mere happening of a crime in which several people participate does not of itself establish a conspiracy among those people.” For example, people do not commit the offense of conspiracy “when they join into an affray spontaneously, rather than pursuant a common plan, agreement, or understanding.” That’s because conspiracy requires a prior agreement. It is not enough that a crime was committed by multiple people because if they all acted spontaneously, then it was not a conspiracy. Conspiracy is a complicated legal charge, and there are many potential defenses other than mere presence and mere participation.

Now back to the original question – does the video show a conspiracy? When looking just at the video posted on the Inquirer’s website, it appears that the city lawyer did not commit the vandalism (which would likely be charged as criminal mischief) himself. Instead, he appears to have continued drinking his wine and taken some photos of the vandalism. Therefore, in order to convict him under a theory of conspiracy, the prosecution would have to show that there was some prior agreement to commit the crime or that based on the conduct in the video, the judge or jury should infer that there was a prior illegal agreement.

Although he watched it happen and even photographed it, those actions may not be enough to show that he planned the vandalism or agreed with the painter to help with it. Simply being there and photographing it may have just been mere presence as explained above, and mere presence is not a crime. This, however, assumes that the two men have not confessed or given statements which indicate that they were both planning on doing it. Assuming that the video would be the only evidence introduced at trial, the judge or jury would not know whether the two men spoke about their plans beforehand and may very well find that there is insufficient evidence of a conspiracy.

Of course, that is the criminal defense lawyer's perspective, and I still strongly advise my readers not to hang around when other people are committing crimes or possessing illegal contraband. The police and prosecutors may view it differently, and whether they feel there is enough evidence to bring charges is a different question from whether the judge or jury should find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The government could argue that there was a conspiracy: the two men appear to arrive together, it looks like they may speak to each other as they leave the scene, the act appears planned because the one man has brought a spray-can which he appears to attempt to conceal under his jacket as they approach, and the city solicitor takes photographs of the act, thereby egging him on and encouraging him to commit the vandalism. There are also other theories of criminal liability such as aiding and abetting which are equally complicated and which I will save for a future article. These decisions will ultimately be made by prosecutors and a judge or a jury, but whether the assistant solicitor committed a crime is not as simple as it initially may seem, and an experienced criminal defense attorney will recognize the available legal defenses even when there is a video of the incident which on its face may look incriminating.

The key takeaway from this post is that criminal charges like conspiracy are complicated. They require a great deal of skill and expertise to identify the issues and raise the right legal and factual defenses. Many people would assume that the Assistant City Solicitor is guilty of vandalism, but as I have explained, there are several defenses which could be raised. The Philadelphia Criminal Defense Attorneys of Goldstein Mehta LLC have handled countless conspiracy cases with great success. We have won cases based on mere presence and mere participation arguments. We know that each case is different, and we always fight for the best possible outcome for each client. If you or a loved one are facing conspiracy or any other criminal charges in Philadelphia or the surrounding counties, call 267-225-2545 for a confidential, honest consultation.

What's the difference between Aggravated Assault and Simple Assault?

We just updated our legal guide to include an in-depth discussion of the different types of Assault charges under Pennsylvania law. Click here to learn more about Aggravated Assault, Simple Assault, Assault on Law Enforcement and Correctional Officers, and the difference between these types of charges. We also provided explanations and examples of some of the many different defenses that may be available to a defendant facing these serious charges.

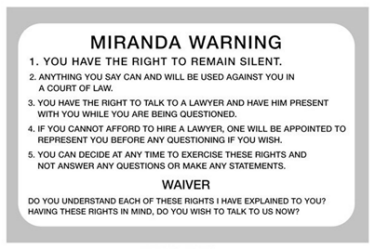

Knowing Your Rights Could Be the Difference Between Decades in Prison and Freedom

In my last post, I wrote about the collateral consequences of a conviction. It is worth repeating that a conviction will follow you for the rest of your life. I feel that I left out an important fact: unlike many other laws dealing with criminal convictions there is no ex-post facto to save you. At any time the legislature can add a collateral consequence that is essentially retroactive. You can be convicted or plead guilty in one decade only to have new rights taken away from you in a different one. This is unlike any other area of criminal law.

That written, I want to add something that is less about law, consequences, or statues and more about your rights as a person when contacted by the police or any other agent of the state.

You have the right to remain silent.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in court.

You have the right to an attorney.

if you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to represent you.

Anyone who has ever watched a police thriller knows that litany. I just typed it out from memory because I’m on a train and there is no internet access (technically there is internet access, it is so slow and spotty it is worse than no internet access). I’m willing to bet good money that anyone reading this knows the litany I’ve written above. Why then do so many people make inculpatory statements to the police? They know they don’t have to, they’ve seen and heard that they have the right to remain silent on TV 1000s times. They know they have the right to an attorney, Law & Order said so.

Here’s the problem: most people want to be useful. They want to help. They think “if I just talk to the police all of this will be cleared up and I can go home.” Maybe - maybe that’s true, but the more likely scenario is that the police officer talking to you and the detective questioning you think you have committed a crime. Why are you helping them? To them this isn’t personal, you’re not their friend. This is business. To put it in the simplest possible terms: if the police had an airtight case - would they bother getting a statement from you. No, because they didn’t need it. Talking to them to “clear the air” will only hurt you.

As a criminal defense attorney, I have never been grateful that a client made a statement. Never, in all the years I have practiced law. Not once. It never helps. You do not have to talk to the police, you do not have to agree to a search of your person or a search of your vehicle, or a search of your home (if the police have warrant, that’s a different story - but you still don’t have to talk to them other than to agree you are who you are).

I can hear people telling me right now, “But Mrs. Mehta - the police told me they don’t need a warrant to search my car.” Technically this is true. In Pennsylvania it was once true that the police needed a warrant to search your vehicle, and then for various reasons, we will not get into here that law changed, but the standard to search your car or vehicle has remained the same, the police still need probable cause to search your car. But you don’t need to make it even easier for them by saying, “sure officer, feel free to search my car, I am absolutely, 100% sure none of my friends have left anything in there that might come back to bite me. I am 150% sure the car I borrowed from my friend, who is always in trouble, is clean.” Refusal to consent to a search does not give rise to probable cause, but just about anything else you say will start to help the police make a case that they had probable cause to search your car/house/person. The police officer might say, “he was being evasive, she seemed nervous, his story kept on changing, she was speaking rapidly.”

And frankly, most of that is probably true. I know when I see red and blue lights behind me on the highway I quickly suss through the last 20 years of my life and briefly wonder if there is some terrible sin I have forgotten or an unpaid ticket that finally made its way into a computer system somewhere.

So what are you to do?

Scenario 1

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: No

You: Am I free to go?

Police: Yes

THEN GO.

And call an attorney.

Scenario 2

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: Yes

You: I would like to speak to my attorney, here is their card.

I would not like to make a statement.

Don’t have a lawyer’s card? Print out mine, carry it with you, know your rights, and know to do when the rest of your life is on the line:

Collateral Consequences - the Impact of a Criminal Case on the Rest of Your Life

After a conviction, most people are not sent to jail. Most people are given probation or no further penalty. And yet, every contact with the criminal justice system is incredibly dangerous and needs to be taken seriously because besides the embarrassment of a criminal record following you around for the rest of your life, you can also lose important rights as a result of that conviction. For many, it isn't the conviction that is the most ruinous, it's the so-called, "collateral consequence."

After a conviction, most people are not sent to jail. Most people are given probation or no further penalty. And yet, every contact with the criminal justice system is incredibly dangerous and needs to be taken seriously because besides the embarrassment of a criminal record following you around for the rest of your life, you can also lose important rights as a result of that conviction. For many, it isn't the conviction that is the most ruinous, it's the so-called, "collateral consequence."

Collateral Consequences are nothing new. They have been a part of legal systems since at least the Ancient Greeks. The Greeks had ἀτιμία, the Romans infamia, and in early English Common law civiliter mortuus (civil death).

In early English Common law, the idea of civil death was pretty simple. You may be physically alive, but you were legally dead. That's to say, upon conviction the Crown completely severed all legal and civil rights. The complete loss of one's civil rights, probably made sense because there was often just one penalty for a felony in early English Common Law: death. Extinguishing the rights of a person might make sense when you were just aligning his (or her) legal rights with the physical rights of his soon to be dead body (that's to say none).

The loss of rights under civil death was total. A convict lost the right to enter into contracts, transmit property by inheritance and devise, marry (or, conversely - remain married as civil death also had the effect of dissolving the marriage), serve as a witness in any court case criminal or civil and vote. Civil death also had the effect of passing what property and estates a convict might have to his or her heirs upon sentencing (often not an issue because the Crown often took all the property) meaning a convicted person had no funds to appeal or fight his case after his conviction.

All in all civil death was harsh and unfair. Clearly, we know better today and civil death isn't a feature in modern American jurisprudence.

Or is it?

In an unending wail to "be tough on crime," simple imprisonment is not considered enough punishment by some. So many states, Pennsylvania in particular, have civil penalties in addition to the criminal ones. These civil penalties are not part of any sentence that is handed down by a court such as incarceration, fines, or probation. They are actions taken by the state and they encompass a wide array of life. And you may not be told anything about them other than, "there may be some consequences."

In Pennsylvania, these collateral consequences (the children of Civil Death) encompass adoption and foster care, child custody, restriction of a professional licenses (or complete loss of that license), loss of a driver's license, employment, the right to serve on a jury, the ability to obtain financial aid, the right to own a firearm, the ability to receive public benefits, the right to subsidized housing. These collateral consequences can even include your legal right to remain in this country or become a U.S. citizen. And while this list might seem broad, it in no way a comprehensive of all collateral consequences.

If, for example, you are convicted of Knowing and Intentional Possession of a Controlled Substance (also known as K&I in Philadelphia) under 35, § 780-113 et. seq. you will also have your driver's license suspended under 75 Pa. C.S. § 1532 for six months for even a first offense. For a third, you will lose it for two years. See: (http://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/LI/consCheck.cfm?txtType=HTM&ttl=75&div=0&chpt=15&sctn=32&subsctn=0)

If you've been convicted of aggravated assault (18 Pa.C.S. § 2702), 18 Pa.C.S. § 6114 (relating to contempt for violation of order or agreement) or 75 Pa.C.S. Ch. 38 (DUI), the court shall consider these convictions if you are involved in a child custody proceeding. Nor is this a complete list; there are many other crimes that will interfere with your ability to keep custody of your children.

If you are convicted of various sex offenses you may not be allowed to live with your children, you may not be allowed to live in certain areas of the city, you may have to "register" with the state police, give your name, your identification, your living address. You may have to have this information posted on a publicly available website. You may be even be banned from taking certain jobs.

If you are convicted of a crime of domestic violence, you will never again be allowed to purchase a gun. This is true even for a misdemeanor conviction.

As you can see, the consequences of a criminal conviction go far beyond incarceration and “a record.” The long term effects are mind boggling and far reaching. You can not and should not go this road alone. If you are currently charged with or could be charged with a crime, then you should contact an attorney as soon as possible. Before you can make any decision you must know all the facts, and to know all the facts, you must speak to an experienced criminal defense attorney.

The Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyers of Goldstein Mehta LLC have extensive experience fighting all types of state and federal charges in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We know the consequences of a conviction and will do everything in our power to prevent one. Call 267-225-2545 now for a free consultation.