Philadelphia Criminal Defense Blog

Can Federal Agents Force You to Give up Your Computer Password?

Whether the government can force a suspect in a criminal investigation to provide the password to a computer or cell phone is an issue which frequently comes up in cases involving illegal pornographic material and other computer crimes. As a general rule, the Fifth Amendment provides the right against self-incrimination, meaning the government cannot compel a suspect or criminal defendant to say something which could lead to criminal liability. However, there are a number of exceptions to this blanket rule, and whether or not the exceptions apply could depend on whether you are being investigated with a crime by federal agents or local police or charged with an offense in state or federal court. This article focuses on a recent Third Circuit decision which allowed federal prosecutors to compel the production of a computer password from a suspect. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, however, has found that a state court may not issue such an order as doing so would violate the Fifth Amendment.

United States v. Apple MacPro Computer

Recently, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held that in at least some circumstances, the police may obtain a court order requiring an individual to produce the password to a computer, hard drive, or cell phone. In United States v. Apple MacPro Computer, the Third Circuit upheld a contempt citation issued against a suspect (John Doe) who was being investigated for child pornography due to the Doe’s refusal to produce the password to certain hard drives which investigators recovered pursuant to a search warrant.

The procedural history of the case is a little bit convoluted, but the facts are fairly straight-forward. During a child pornography investigation, Delaware County investigators executed a search warrant on Doe’s residence. They recovered a number of phones, computers, and hard drives. Federal agents subsequently obtained a search warrant to examine the seized devices. Doe provided the password for one of the phones, but he refused to provide the passwords to various other devices. Forensic examination of one of Doe’s computers showed evidence that the computer had been used to access child pornography, but investigators were not able to view the full contents of the computer without the password because of encryption on the device.

In addition to seizing and examining the computers, the Delaware County investigators interviewed Doe’s sister. Doe’s sister confirmed that she had previously lived with Doe and Doe had actually shown her hundreds of images of child pornography on the encrypted hard drives. She also told investigators that Doe had videos of children engaged in sex acts on the devices.

Based on this showing, the federal investigators obtained an order under the All Writs Act compelling Doe to provide the relevant passwords. The All Writs Act is a relatively obscure federal statute which gained notoriety during the investigation of the San Bernadino terrorist attack when the FBI sought to compel Apple to unlock the attacker’s iPhone. It permits federal courts to “issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.” Under the Act, federal courts may issue orders “as may be necessary or appropriate to effective and prevent the frustration of” previously issued orders in cases in which the court already had jurisdiction.

Doe filed a Motion to Quash the order, arguing that the order violated his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. The federal court denied the Motion to Quash and directed Doe to unlock the devices for the investigators. Doe did not appeal, but he refused to unlock some of the devices, claiming that he had forgotten the passwords. He was eventually held in contempt by the District Court, and the Court ordered that he remain in federal custody until he was willing to unlock the devices.

The Third Circuit’s Ruling

On appeal, the Third Circuit affirmed the District Court’s ruling. Due to the unusual procedural posture of the case, the Third Circuit applied a highly deferential plain error standard of review to the District Court’s decision. First, the Third Circuit panel found that the District Court had properly issued the order under the All Writs Act. Second, the Third Circuit agreed that ordering Doe to unlock the phone would not violate his Fifth Amendment rights because of the “foregone conclusion” exception to the Fifth Amendment. Noting that the Fifth Amendment applies only when the accused is compelled to make a testimonial communication that is incriminating, the Third Circuit recognized that the mere act of producing evidence such as a physical object or some type of records in response to a subpoena or court order can be incriminating because the act of production concedes the existence of the evidence and the possession and control thereof by the defendant. In that situation, the Fifth Amendment applies and would prevent compelled production of evidence.

What is the foregone conclusion doctrine?

However, there is also a “foregone conclusion” exception. The Fifth Amendment does not protect an act of production when the existence, custody, and authenticity of the evidence is a “foregone conclusion” that “adds little or nothing to the sum total of the Government’s information.” Thus, because the government could prove through the forensic examination of the devices and the testimony of Doe’s sister that 1) the devices existed and the Government already had custody of them, 2) Doe possessed, accessed, and owned all the devices, and 3) there was child pornography on the devices, the foregone conclusion doctrine applied. Therefore, the Third Circuit affirmed the District Court’s finding of contempt.

As the case makes clear, the issue of whether a suspect or criminal defendant can be compelled to produce a password is not totally settled, and it depends heavily on the facts involved. In cases where the government can prove that the defendant had ownership of the devices and used them to view child pornography or that they contain some other critical evidence, the government may be able to punish a defendant who refuses to unlock the device. However, in many cases, this will be a difficult showing for the government to make as the government will not often have witnesses like Doe’s sister who observed the defendant viewing the child pornography or damaging admissions from the defendant about who owned the devices. Likewise, it is very important that the government was able to determine that the devices contained contraband even on the unencrypted portions of the drives.

Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyers Demetra Mehta and Zak Goldstein

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Attempted Murder. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

PA Superior Court: Villanova University Campus Safety Officers Can Search Your Room

Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak Goldstein

The Pennsylvania Superior Court has decided the case of Commonwealth v. Yim, holding that the Villanova Public Safety Officers are not state agents for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. This is a significant decision for those who attend private universities which do not have police forces because it means that campus safety officers may be able to search a dorm room without a search warrant.

Commonwealth v. Yim

On February 13, 2016, Villanova University’s Public Safety Officers became engaged in violent confrontations with two resident students and a female visitor who later admitted to ingesting LSD. These three individuals were restrained by the public safety officers until Radnor Police Officers arrived on scene. One of the residents lived at Good Counsel Hall, which is located on Villanova’s campus, with the defendant. It is important to note that although Villanova has now established an actual police force, at the time, its officers were not police. They did not have arrest powers or carry weapons or handcuffs. Further, Villanova is a private university.

As a condition of living at Good Counsel Hall, the defendant had signed a housing contract in which he consented to a search of a dorm room where it has been determined by public safety officers that items or individuals in a particular room pose a possible safety or health risk to the community. Later that day, the Villanova University Director of Public Safety was advised of the events that transpired involving the defendant’s roommate. The administration subsequently ordered a search of the defendant’s room.

Prior to searching the room, the administrators unsuccessfully attempted to contact the defendant by telephone. The Director of Public Safety, along with two Public Safety Officers, unlocked and entered the dorm room. Once inside, they observed contraband and cash strewn throughout the room. They saw a syringe in plain view on top of a desk. The defendant’s passport, cash, LSD “stamps”, marijuana, $8,865.00, and other drug paraphernalia was also found on and in the defendant’s desk.

After the contraband was recovered, the Director of Public Safety called the Villanova University dispatcher and asked him to contact the Radnor Police Department to report the discovery of the drugs and paraphernalia. The Radnor Police arrived on scene, but they remained in the hall outside the room. The police officers never entered the room nor did they participate in the search. After the public safety officers searched the room, they turned over the contraband and other items to the Radnor Police. The Public Safety Officers also provided an investigative report, which included photographs, for future use in University administrative proceedings. The police then obtained an arrest warrant for the defendant. He was eventually arrested and charged with possession of a controlled substance, possession of drug paraphernalia, and possession with the intent to deliver (“PWID”).

The defendant filed a motion to suppress the evidence seized from his person and the dorm room. The trial court denied the motion, ruling that the public safety officers did not need a search warrant to search the dorm room because they were not law enforcement officers and Villanova was not a public university. The trial court found the defendant guilty after a non-jury trial and sentenced him to a term of three to 23 months’ incarceration plus four years probation.

What is the Fourth Amendment?

The Fourth Amendment provides:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The Fourth Amendment often provides a defense to criminal charges relating to drug possession, illegal gun possession, or the possession of other contraband because it prevents the prosecution from introducing evidence at trial if the evidence was seized illegally. However, one significant limit on the Fourth Amendment is that it does not apply to searches and seizures conducted by other private citizens. It only protects citizens from the government; it does not protect them from private actors. Thus, the Fourth Amendment may be invoked as part of a motion to suppress evidence when the when a government actor like a police officer enters an individual’s home without a search warrant or stops someone without probable cause or reasonable suspicion. In this case, however, the officers who seized the contraband from the dorm room did not work for the government. They were not police officers performing a government function and Villanova is a private school.

Can the Fourth Amendment Apply to Non-State Actors?

In some circumstances, the Fourth Amendment can apply even to non-government employees. For example, the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures do apply to non-state actors when private individuals act as an instrument or agent of a state. Here, the defendant argued at the motion to suppress that Villanova’s public safety department had assumed a governmental function and essentially acted as the police. Accordingly, the defense argued that the public safety officers should be treated as state actors. Unfortunately, cooperation with the authorities alone does not constitute state action. The mere fact that the police and prosecutors use the results of a private actor’s search does not transform the private action into a state action. Instead, it must be shown that the relationship between the person committing the wrongful acts and the state is such that those acts can be viewed as emanating from the authority of the state. This means that if a college or university forms an actual police department with certified officers who have arrest powers, then the Fourth Amendment should apply to those officers. Likewise, the Fourth Amendment may apply to the public safety department of a public university because the officers would be government employees. Here, however, the officers were not actual police officers or government employees.

Can Campus Safety Officers Search a Dorm Room Without a Warrant?

Ultimately, the Pennsylvania Superior Court affirmed the suppression court’s denial of the defendant’s motion to suppress. The Superior Court found that the University conducted the search on its own terms and in accordance with its own policies aimed at preserving student safety. The public safety department did not act jointly with the police or at the behest of the police in carrying out the search. Additionally, the public safety department had not assumed a governmental function such that it should be subject to the Fourth Amendment because the Radnor Township Police Department still served as the actual police force on university property. The court denied the appeal, and the defendant will not receive a new trial.

Facing Criminal Charges? We Can Help.

Goldstein Mehta LLC

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Possession with the Intent to Deliver, Aggravated Assault, and Attempted Murder. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

The police want to ask me some questions. Should I talk to the police?

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Do I have to talk to the police?

One of the most common questions I receive as a criminal defense lawyer is whether or not you should talk to the police. Almost every day I get a phone call from someone who just found out that the police are looking for them or want to ask them questions, and they want to know what to do. Many people think they either have to go give a statement or that they will help themselves by giving a statement. That is almost always the wrong answer. I have defended thousands of cases, and I can probably count on one hand the number of times that a client has helped themselves by giving a statement.

When I get this question, my advice is almost always the same: if the police are looking for you or want to talk to you, you should consult with an experienced criminal defense attorney before you talk to the officer. Only a criminal defense lawyer can evaluate your circumstances and help you avoid doing something to make the situation worse. The consequences of a criminal arrest and conviction can be life-changing. Given the overwhelming power of the government and almost unlimited resources of the police and prosecutor, there is very little room for error when dealing with a potential criminal prosecution. I have represented countless clients who would not have even been arrested had they not made an incriminating statement under the belief that it would help their situation. Many people think that they will be able to talk themselves out of trouble or that the police officer will understand. That is almost never the case. Therefore, I always advise anyone who asks that they should talk to a criminal defense lawyer first.

Why are the police looking for me?

If you are a potential suspect in a crime, there are generally two reasons why the police may be looking for you and would come to your house or call you on the phone. First, it is possible that the officer has already obtained a warrant for your arrest. Second, the officer may still be investigating the case and would like to interview you in order to obtain potentially incriminating evidence. It does not matter in which case you find yourself. If the police want to talk to you, you need to speak with a criminal defense lawyer before you agree to an interview with a police officer. This is true even if you believe that you have not done anything illegal.

In the first situation, if the police have a warrant for your arrest, they may come to your house or call your family members in order to find you and execute the arrest warrant. If they are having trouble finding you or you are not home when they come out to the house, the officers often may not reveal that they have already obtained a warrant for fear that you will take off or attempt to destroy evidence before they can find you. In many cases, you or your family will simply be told that they want you to come down to the station to answer some questions and clear things up. However, this does not mean that they have not already obtained an arrest warrant. For this reason, you should always consult with an attorney before agreeing to give any kind of statement. An attorney will often be able to verify that the police have obtained a warrant and arrange for you to turn yourself in so that there are no dangerous incidents with the police. Most importantly, once the police know that you have retained an attorney for that particular matter, they cannot question you and attempt to elicit incriminating statements. In many cases, an unhelpful statement is the difference between going to jail and avoiding prosecution altogether.

Should I talk to the police without a lawyer?

For this reason, if the police have a warrant or are looking for you, you should not make any statements because those statements will be used against you in court. Instead, you should contact an attorney who can verify that a warrant exists and make arrangements for you to turn yourself in. In addition to making sure that the police do not attempt to interrogate you, there are other significant benefits to retaining counsel and turning yourself in.

Do I need a lawyer for preliminary arraignment?

When you retain a criminal lawyer and turn yourself in, the magistrate is likely to set bail at a lower amount a the preliminary arraignment because the fact that you retained counsel and voluntarily turned yourself in shows that you are not a flight risk and are prepared to answer to the charges. On the other hand, if you fail to turn yourself in, the prosecutor may argue that you are a flight risk and seek higher bail. At trial, the prosecutor may ask for a flight instruction in which the judge will tell the jury that flight could be construed by the members of the jury as consciousness of guilt. Therefore, if you believe that you are under investigation or learn that the police have obtained a warrant, you should always retain an attorney before turning yourself in or giving any kind of statement.

The second situation occurs when the police are still in the investigatory stage of the case. They may view you as a suspect, but they may feel that they do not yet have enough evidence to bring formal criminal charges. Given the fact that there are thousands of state and federal criminal statutes and the fact that many people who face criminal prosecution are actually innocent, it is entirely possible for you to be a suspect in a crime and fully believe that you have not done anything wrong. Given the number of criminal statutes, it is easily possible to violate a criminal law without even knowing that the law existed. Even in cases where you believe you have not committed a crime, it is best to consult with an attorney first in order to avoid any misunderstandings or saying anything that could implicate you in the crime.

Do I need an attorney if I have not been charged yet?

If the investigation is still ongoing, it is possible that the police could view you as a suspect when you are only a witness, and an attorney may be able to take proactive steps to clear up any misunderstandings before it is too late and the police file charges. Likewise, you may not know what information the police already have, and you could say something incriminating due to faulty memory, embarrassment, or by contradicting other solid evidence that they have by accident. Even if you tell the complete truth, it is entirely possible for the officer to make an error in typing up the statement or misunderstand what is said, and that error could be used against you at a later date. Criminal investigations and charges are extremely serious, and the stakes are too high to simply give a statement without the advice of counsel.

The most important thing to remember is that if the police have enough evidence to charge you, you are never going to talk yourself out of it. The most you can say is that you did not do it, and they are not likely to believe you. If they do not have enough evidence to charge you, then you do not want to help them collect that evidence by giving an incriminating statement. If you have indisputable proof of an alibi, then your attorney can turn that over without you having to make a statement. Further, if the police really want to talk to you, a criminal defense lawyer may be able to help you obtain something valuable in exchange such as immunity for cooperation or a reduced charge or sentence in exchange for the statement. An attorney will be able to get a promise in writing and it will be binding, whereas promises the police make to you are not necessarily enforceable in court. Likewise, your attorney may be able to arrange for an off-the-record proffer session in which the statement cannot be used against you as substantive in court unless you later testify to something different at trial.

Due to recent decisions of the United States Supreme Court, simply remaining silent is not always the best way to protect your rights. You should always assert that you would like to speak with an attorney before being questioned. It is always best to consult with a criminal defense attorney so that you can protect your constitutional rights before having any interaction with law enforcement. It is easy to accidentally waive important rights, and once they are waived, it is not always possible to undo the damage.

A PHILADELPHIA DEFENSE LAWYER CAN HELP

If the police are looking for you or you may be the subject of a criminal investigation, you need to speak with one of our criminal defense lawyers. We can help advise you on whether it makes sense to give a statement or whether you should assert your Fifth Amendment rights. In most cases, you will be better off remaining silent. In every case, you should invoke your right to remain silent until you have spoken with one of our criminal defense attorneys. Call 267-225-2545 today for a complimentary 15-minute criminal defense strategy session.

CONTACT A CRIMINAL DEFENSE ATTORNEY IN PHILADELPHIA TODAY

Knowing Your Rights Could Be the Difference Between Decades in Prison and Freedom

In my last post, I wrote about the collateral consequences of a conviction. It is worth repeating that a conviction will follow you for the rest of your life. I feel that I left out an important fact: unlike many other laws dealing with criminal convictions there is no ex-post facto to save you. At any time the legislature can add a collateral consequence that is essentially retroactive. You can be convicted or plead guilty in one decade only to have new rights taken away from you in a different one. This is unlike any other area of criminal law.

That written, I want to add something that is less about law, consequences, or statues and more about your rights as a person when contacted by the police or any other agent of the state.

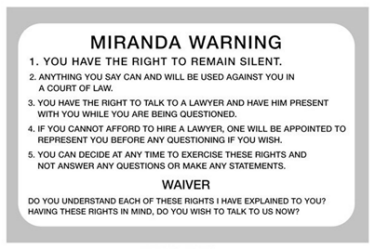

You have the right to remain silent.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in court.

You have the right to an attorney.

if you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to represent you.

Anyone who has ever watched a police thriller knows that litany. I just typed it out from memory because I’m on a train and there is no internet access (technically there is internet access, it is so slow and spotty it is worse than no internet access). I’m willing to bet good money that anyone reading this knows the litany I’ve written above. Why then do so many people make inculpatory statements to the police? They know they don’t have to, they’ve seen and heard that they have the right to remain silent on TV 1000s times. They know they have the right to an attorney, Law & Order said so.

Here’s the problem: most people want to be useful. They want to help. They think “if I just talk to the police all of this will be cleared up and I can go home.” Maybe - maybe that’s true, but the more likely scenario is that the police officer talking to you and the detective questioning you think you have committed a crime. Why are you helping them? To them this isn’t personal, you’re not their friend. This is business. To put it in the simplest possible terms: if the police had an airtight case - would they bother getting a statement from you. No, because they didn’t need it. Talking to them to “clear the air” will only hurt you.

As a criminal defense attorney, I have never been grateful that a client made a statement. Never, in all the years I have practiced law. Not once. It never helps. You do not have to talk to the police, you do not have to agree to a search of your person or a search of your vehicle, or a search of your home (if the police have warrant, that’s a different story - but you still don’t have to talk to them other than to agree you are who you are).

I can hear people telling me right now, “But Mrs. Mehta - the police told me they don’t need a warrant to search my car.” Technically this is true. In Pennsylvania it was once true that the police needed a warrant to search your vehicle, and then for various reasons, we will not get into here that law changed, but the standard to search your car or vehicle has remained the same, the police still need probable cause to search your car. But you don’t need to make it even easier for them by saying, “sure officer, feel free to search my car, I am absolutely, 100% sure none of my friends have left anything in there that might come back to bite me. I am 150% sure the car I borrowed from my friend, who is always in trouble, is clean.” Refusal to consent to a search does not give rise to probable cause, but just about anything else you say will start to help the police make a case that they had probable cause to search your car/house/person. The police officer might say, “he was being evasive, she seemed nervous, his story kept on changing, she was speaking rapidly.”

And frankly, most of that is probably true. I know when I see red and blue lights behind me on the highway I quickly suss through the last 20 years of my life and briefly wonder if there is some terrible sin I have forgotten or an unpaid ticket that finally made its way into a computer system somewhere.

So what are you to do?

Scenario 1

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: No

You: Am I free to go?

Police: Yes

THEN GO.

And call an attorney.

Scenario 2

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: Yes

You: I would like to speak to my attorney, here is their card.

I would not like to make a statement.

Don’t have a lawyer’s card? Print out mine, carry it with you, know your rights, and know to do when the rest of your life is on the line: