Philadelphia Criminal Defense Blog

PA Superior Court: Defendant Must Be Permitted To Rebut Commonwealth's 404(b) Prior Bad Acts Evidence

The Pennsylvania Superior Court has just decided the case of Commonwealth v. Yocolano, holding that the defendant's conviction must be reversed because the trial court improperly prevented the defendant from rebutting the Commonwealth's 404(b) Prior Bad Acts evidence. Under the Pennsylvania Rules of Evidence, prosecutors may file a motion asking the trial court to allow them to introduce evidence of "prior bad acts" or crimes committed by a defendant. This type of evidence can be extremely prejudicial to the defendant, and the Superior Court has now ruled that the defense must be permitted to call witnesses to rebut this highly prejudicial testimony when such witnesses are available.

Commonwealth v. Yocolano

In Yocolano, the defendant was charged with Aggravated Assault and various sexual assault charges against his paramour, who is referred to in the opinion as A.A. The testimony established that Mr. Yocolano and A.A. were in an on-again, off-again romantic relationship dating back to 2010 and had a child together. Throughout their relationship, there were multiple alleged instances of domestic violence. The police were called on several occasions. For example, in 2010, the police responded to a call that Mr. Yocolano had an altercation with A.A. where he chased her and caused damage to A.A.’s father’s house. In 2012, the police were called on several occasions including: an incident where police were called after Mr. Yocolano threatened A.A. with a machete; an argument between A.A. and Mr. Yocolano; A.A. calling the police on Mr. Yocolano after expressing suicidal thoughts after an argument between the two; A.A. filing a police report against Mr. Yocolano after he threatened and choked her; and Mr. Yocolano punching A.A. in the head and threatening to kill her and her family. In October of 2012, A.A. obtained a Protection from Abuse “PFA” against Mr. Yocolano. This incident led to the charges in question, and Mr. Yocolano was subsequently arrested.

Both before and during the trial, the Commonwealth filed multiple 404(b) motions in Mr. Yocolano’s case. Specifically, the Commonwealth sought to introduce evidence from the 2010 incident and three incidents from 2012. The prosecutors also sought to introduce two PFA’s against Mr. Yocolano filed by women other than A.A. on the fourth day of trial, and the trial court permitted the prosecution to introduce all of the prior bad acts evidence.

What is a 404(b) Prior Bad Acts Motion?

In most cases, a prosecutor may only use evidence against a defendant relating to the crimes alleged in the complaint. This means that prosecutors cannot simply tell a judge or jury that the defendant is a criminal or has a criminal record. A 404(b) Motion, commonly referred to as a “Prior Bad Acts Motion,” allows the Commonwealth to introduce prior acts against a defendant in the present criminal case against him under certain limited circumstances. A 404(b) motion cannot be used to prove a person’s character (i.e. that because a defendant did something bad once in their life, they are a bad person and thus did this crime), but rather it can be used to show motive, opportunity, intent, absence of mistake, knowledge, lack of accident, preparation, and plan. In domestic violence cases, 404(b) motions are common, and appellate courts have held that in some cases, they may be used to show “the continual nature of abuse and to show the defendant’s motive, malice, intent and ill-will toward the victim.” Commonwealth v. Ivy, 146 A.3d 241, 251 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2016). Accordingly, prosecutors routinely argue that prior convictions or allegations of violence between the defendant and the complainant provided the defendant with the motive for the criminal behavior alleged in the current case or would show that the injuries could not have been caused as the result of an accident.

Defending Against 404(b) Motions

Obviously, prosecutors gain a tremendous advantage when they are permitted to inform a judge or jury of a defendant's prior record. The judge or jury become much less likely to be sympathetic and far more likely to believe that if the defendant committed a crime before, he or she must have committed a crime again. However, it is possible in many cases to successfully oppose these motions or limit the damage. In some cases, it may be possible to show a lack of similarity between the conduct or that the prejudicial effect would substantially outweigh any probative value. It also may be possible to successfully argue that the prior conviction does not establish any of the requirements which the Commonwealth must show. In other cases, it may be possible to call eyewitness from the other incidents to show that the other allegations are also false. Therefore, if you are charged with a crime and a prosecutor is seeking to introduce prior bad acts against you, it is imperative that you have a skilled attorney who can litigate a motion to prevent these prior bad acts from being introduced into trial or attempt to limit the damage by thoroughly investigating the allegations. In Mr. Yocolano’s case, his attorney was unsuccessful in opposing the three incidents from 2012, the incident from 2010, and the prior PFA’s which were filed by other women.

Although the defense could not keep this highly prejudicial evidence out, the defense had thoroughly investigated the case and located a number of witnesses which were ready to rebut the prior bad act allegations. During the trial, the defense attempted to introduce evidence that would rebut the 2010 incident. However, the trial court precluded the defense from introducing evidence to rebut the claim, holding that it was “collateral.” Specifically, the trial court only allowed the defendant to introduce evidence that would rebut the allegations from December 6, 2012 (the day on which the crimes for which he was on trial allegedly took place) and was not allowed to introduce any evidence that would rebut the “prior bad acts” that the trial court had found admissible. Given all of this prejudicial testimony from other incidents, the defendant was ultimately convicted and sentenced to 18-36 years of incarceration.

Yocolano appealed, and the Superior Court reversed the conviction. The Court found that the trial court abused its discretion in preventing Mr. Yocolano from introducing evidence that would rebut these claims. The Superior Court cited an important Pennsylvania Supreme Court case called Commonwealth v. Ballard which held that “where the evidence proposed goes to the impeachment of the testimony of his opponent’s witness, it is admissible as a matter of right.” The Superior Court properly recognized that Mr. Yocolano should have been allowed to “test the veracity of A.A.’s version of events.”

Protection from Abuse Orders and Rule 404(b)

The Superior Court also held that the trial court abused its discretion when it permitted the two PFA’s from different women to be introduced. Rule 404(b)(3) states that a prosecutor must provide “reasonable notice” if they seek to introduce these prior bad acts. Reasonable notice typically means that the prosecution must inform the defense in writing and in advance of the intent to introduce prior bad acts evidence. There are exceptions which allow the prosecution to introduce prior bad acts during trial where the prosecution can show good cause for the failure to provide prior notice.

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for prosecutors to provide the defense with previously undisclosed evidence on the day of trial. Most judges will either permit the defendant to continue the case or preclude the last-minute evidence from being introduced. However, in this case, the Commonwealth provided the unrelated Protection from Abuse Orders against Mr. Yocolono on the fourth day of trial. The Commonwealth stated that the reason for the late discovery was because the prosecutor had just looked in the computer system mid-trial and happened to find the records.

The Superior Court rejected the Commonwealth's argument that this constituted good cause. The Court held that the Commonwealth’s excuse did “not qualify as a valid legal excuse.” Further, the Superior Court was skeptical that these third-party PFA’s would have met the substantive requirements of 404(b). In Mr. Yocolono’s case, the trial court failed to analyze the facts of the two other PFA’s and identify “a close factual nexus sufficient to demonstrative the connective relevance of the third-party PFAs to the crimes in question.” Based on all of these errors, the Superior Court ordered that the sentence be vacated and that the defendant receive a new trial.

Facing Criminal Charges? We Can Help

Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyers Demetra Mehta, Esq. and Zak T. Goldstein, Esq.

Domestic violence and other assault cases are often more complicated than they would seem. In cases where the prosecution seeks to introduce prior bad acts evidence, the defense must thoroughly investigate the case and strongly oppose these 404(b) motions both on the law and on the facts. If you are facing criminal charges, you need an attorney who has the knowledge and expertise to defend your case. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers have successfully fought countless cases at trial and on appeal. We offer a 15-minute criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to discuss your case with an experienced and understanding criminal defense attorney today.

PA Supreme Court: Retroactive Application of SORNA (Megan's Law) Unconstitutional

BREAKING NEWS: In the case of Commonwealth v. Muniz, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has ruled that Pennsylvania’s Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) may not be applied retroactively without violating the Pennsylvania and United States Constitutions. In this new ruling, the Court held:

SORNA’s registration provisions constitute criminal punishment;

Retroactive application of SORNA’s registration provisions violates the federal ex-post facto clause, and

Retroactive application of SORNA’s registration provisions also violates the ex-post facto clause of the Pennsylvania Constitution.

I will write more about the reasoning of this ruling in a later blog post, but for now, the ruling is so ground breaking that we wanted to post this news as quickly as possible.

As some readers have learned through terrible experience, Pennsylvania law required many people to register as sex offenders either a) long after they had completed their sentence and probation, or b) to start registering as a sex offenders even when the offense to which pleaded or were found guilty was not an offense that required registration at the time. Many others found that they had pleaded or been found guilty to offenses which required ten years of registration or even no registration only to learn after a few years that ten years of registration had become a lifetime of Megan's Law registration.

Prior to this new opinion, the Pennsylvania Superior Court repeatedly found that SORNA’s registration provisions should not be considered punishment. Therefore, retroactive application of registration requirements for those convicted of sex offenses prior to SORNA’s effective date did not violate either the federal or state ex-post facto clauses.

As anyone who has been required to register knows, sex offender registration is one of the most severe punishments the law can impose. It is second only to incarceration, and in many cases, may be worse. Sex offender registration requires regular meetings with the State Police, prohibits contact with children (even when the original conviction had nothing to do with children and may not have even involved a sexual act of any kind), and results in the offender's image, place of employment, address, and vehicles being placed on the State Police website for the world to see. Given the severity of the punishment, particularly in the case of lifetime registration, countless people would have taken their cases to trial had they known at the time of the plea that they would later be required to register for life instead of for ten years or not at all. The risk of trial may have been well worth the reward of avoiding lifetime registration. This new ruling should bring relief to those in the position.

This ruling should also help those who were originally required to register as Tier I & Tier II offenders but who have now been informed their offense is now a Tier III offense (required lifetime registration and check-ins with the state police every three months.)

If you pleaded guilty to a crime and were originally not required to register at all or were required to register only for a limited period of time and later found out that your tier changed, call us. We may very well be able to assist you. Your consultation is 100% free and confidential. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with a Philadelphia criminal defense lawyer today.

Appealing PA Megan's Law Retroactivity Provisions

PA Megan's Law Retroactivity

As Attorney Zak Goldstein previously wrote, Pennsylvania has seen significant changes in the laws governing sex offender registration. Specifically, recent cases have provided some hope for a limited number of Megan's Law and SORNA registrants to downgrade from Tier III lifetime offenders to lower tiers depending on the circumstances of their cases and pleas. Registrants who meet very specific conditions may have the possibility of obtaining a reduced Tier if they can show that they either committed multiple Tier I or Tier II offenses as part of the same case or, in limited circumstances, that the Commonwealth has violated a plea bargain by retroactively requiring the offender to register at a higher tier.

Potential Ways to Lower Megan's Law Tier in PA

Aside from the issues written about in that previous post, there are other ways for a person, required to register under SORNA, to downgrade their registration status or even remove it completely, and that is to enforce the plea that was bargained for at the time of sentencing. It isn't unusual for us to see cases where a defendant has specifically bargained for Tier I registration as part of an agreement to plead guilty. Pennsylvania courts have upheld that such agreements are governed by contract law and enforceable under contract law. This means that, while the offense pleaded guilty to may require higher registration, even lifetime registration the agreement, made at the time of the plea, will often be the deciding factor on how long a someone will have to register. But we've often found when someone is released from prison or from supervision they've been told their registration status has been changed to lifetime registration or from Tier I to Tier III. It may be possible to challenge such a change to one's SORNA registration requirements. However, it can be expensive and difficult, and success is never guaranteed.

information on the Adam Walsh Act (SORNA)

As of 2012, Pennsylvania substantially implemented Title I of the Adam Walsh Act, the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). SORNA requires that offenders register for a duration of time based on the tier of the offense of conviction. Specifically, SORNA requires Tier I offenders register for 15 years, Tier II offenders register for 25 years, and Tier III offenders register for life.

SORNA requires that offenders make in-person appearances at the registering agency based on the tier of the offense of conviction. Specifically, this Act requires that Tier I offenders appear once a year, that SORNA Tier II offenders appear every six months, and Tier III offenders appear every three months. SORNA requires that each jurisdiction maintain a public sex offender registry website and publish certain registration information on that website.

PENNSYLVANIA MEGAN'S LAW REGISTRATION TIERS

Pennsylvania has three categories of registrants for purposes of duration of registration requirements and frequency of reporting to law enforcement for verification:

Tier I offenders, who are required to appear annually to verify registration information and register for a period of 15 years.

Tier II offenders, who are required to appear every 180 days to verify registration information and register for a period of 25 years.

Tier III offenders, who are required to appear every 90 days to verify registration information and register for life.

SORNA Tier I requires offenders to register for a minimum of 15 years and annually verify registration information. The following offenses listed in Pennsylvania Statutes would require, at a minimum, Tier I registration requirements under SORNA:

18 Pa. C.S. § 2902 – Unlawful restraint (non-parental, victim under 18)

18 Pa. C.S. § 2903 – False imprisonment (non-parental, victim under 18)

18 Pa. C.S. § 2904 – Interference with custody of children (non-parental, victim under 18)

18 Pa. C.S. § 2910 – Luring a child into a motor vehicle or structure

18 Pa. C.S. § 3124.2 – Institutional sexual assault (adult victim)

18 Pa. C.S. § 3126 – Indecent assault where the offense is graded as a misdemeanor of the first degree or higher (if punishment less than one year)

18 Pa. C.S. § 6312[d] – Sexual abuse of children (possession of child pornography)

18 Pa. C.S. § 7507.1 – Invasion of privacy

SORNA Tier II requires offenders register for a minimum of 25 years and semiannually verify registration information. The following offenses listed in Pennsylvania Statutes would require, at a minimum, Tier II registration:

18 Pa. C.S. § 3124.2 – Institutional sexual assault (victim age 16-17)

18 Pa. C.S. § 3126 – Indecent assault where the offense is graded as a misdemeanor of the first degree or higher (if recidivist or punishment greater than one year)

18 Pa. C.S. § 5902[b] – Prostitution and related offenses, where the actor promotes the prostitution of a minor

18 Pa. C.S. § 5903[a] [3], [4], [5], or [6] – Obscene and other sexual materials and performances, where the victim is a minor

18 Pa. C.S. § 6312[b], [c] – Sexual abuse of children (production/distribution of child pornography)

18 Pa. C.S. § 6318 – Unlawful contact with minor

18 Pa. C.S. § 6320 – Sexual exploitation of children SORNA

Tier III Offenses requires lifetime registration and quarterly verifications. The following offenses listed in Pennsylvania Statutes would require, at a minimum, Tier III registration requirements under SORNA:

18 Pa. C.S. § 2901 – Kidnapping, where the victim is a minor (non-parental)

18 Pa. C.S. § 3121 – Rape • 18 Pa. C.S. § 3122.1 – Statutory sexual assault

18 Pa. C.S. § 3123 – Involuntary deviate sexual intercourse

18 Pa. C.S. § 3124.1 – Sexual assault • 18 Pa. C.S. § 3124.2 – Institutional sexual assault (victim under 16)

18 Pa. C.S. § 3125 – Aggravated indecent assault

18 Pa. C.S. § 3126 – Indecent assault where the offense is graded as a misdemeanor of the first degree or higher (if victim under 13 and punishment greater than one year)

18 Pa. C.S. § 4302 – Incest (victim under 13, or victim 13-18 years old, and offender more than 4 years older)

HOW OUR PENNSYLVANIA MEGAN'S LAW LAWYERS CAN HELP

Demetra Mehta, Esq. - PA Megan's Law Attorney

If you think you have been required to register for the wrong tier, please contact us to discuss your case. After a brief consultation, we may be able to advise you how to best move forward. If we think we can be of assistance we will investigate your case and offer an opinion on if a challenge to your registration requirements will be successful. We offer a free phone consultation in these matters, and if further investigation is warranted, we typically charge a reasonable initial fee to obtain court records and transcripts, investigate the case, and determine the likelihood of success.

Charged with a crime? Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers have successfully defended thousands of cases. Call 267-225-2545 for a complimentary 15-minute criminal defense strategy session.

Knowing Your Rights Could Be the Difference Between Decades in Prison and Freedom

In my last post, I wrote about the collateral consequences of a conviction. It is worth repeating that a conviction will follow you for the rest of your life. I feel that I left out an important fact: unlike many other laws dealing with criminal convictions there is no ex-post facto to save you. At any time the legislature can add a collateral consequence that is essentially retroactive. You can be convicted or plead guilty in one decade only to have new rights taken away from you in a different one. This is unlike any other area of criminal law.

That written, I want to add something that is less about law, consequences, or statues and more about your rights as a person when contacted by the police or any other agent of the state.

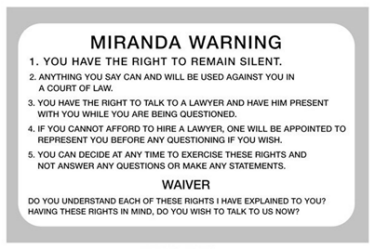

You have the right to remain silent.

Anything you say can and will be used against you in court.

You have the right to an attorney.

if you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to represent you.

Anyone who has ever watched a police thriller knows that litany. I just typed it out from memory because I’m on a train and there is no internet access (technically there is internet access, it is so slow and spotty it is worse than no internet access). I’m willing to bet good money that anyone reading this knows the litany I’ve written above. Why then do so many people make inculpatory statements to the police? They know they don’t have to, they’ve seen and heard that they have the right to remain silent on TV 1000s times. They know they have the right to an attorney, Law & Order said so.

Here’s the problem: most people want to be useful. They want to help. They think “if I just talk to the police all of this will be cleared up and I can go home.” Maybe - maybe that’s true, but the more likely scenario is that the police officer talking to you and the detective questioning you think you have committed a crime. Why are you helping them? To them this isn’t personal, you’re not their friend. This is business. To put it in the simplest possible terms: if the police had an airtight case - would they bother getting a statement from you. No, because they didn’t need it. Talking to them to “clear the air” will only hurt you.

As a criminal defense attorney, I have never been grateful that a client made a statement. Never, in all the years I have practiced law. Not once. It never helps. You do not have to talk to the police, you do not have to agree to a search of your person or a search of your vehicle, or a search of your home (if the police have warrant, that’s a different story - but you still don’t have to talk to them other than to agree you are who you are).

I can hear people telling me right now, “But Mrs. Mehta - the police told me they don’t need a warrant to search my car.” Technically this is true. In Pennsylvania it was once true that the police needed a warrant to search your vehicle, and then for various reasons, we will not get into here that law changed, but the standard to search your car or vehicle has remained the same, the police still need probable cause to search your car. But you don’t need to make it even easier for them by saying, “sure officer, feel free to search my car, I am absolutely, 100% sure none of my friends have left anything in there that might come back to bite me. I am 150% sure the car I borrowed from my friend, who is always in trouble, is clean.” Refusal to consent to a search does not give rise to probable cause, but just about anything else you say will start to help the police make a case that they had probable cause to search your car/house/person. The police officer might say, “he was being evasive, she seemed nervous, his story kept on changing, she was speaking rapidly.”

And frankly, most of that is probably true. I know when I see red and blue lights behind me on the highway I quickly suss through the last 20 years of my life and briefly wonder if there is some terrible sin I have forgotten or an unpaid ticket that finally made its way into a computer system somewhere.

So what are you to do?

Scenario 1

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: No

You: Am I free to go?

Police: Yes

THEN GO.

And call an attorney.

Scenario 2

PO: Sir, we’d like to speak to you.

You: Officer, am I under arrest?

PO: Yes

You: I would like to speak to my attorney, here is their card.

I would not like to make a statement.

Don’t have a lawyer’s card? Print out mine, carry it with you, know your rights, and know to do when the rest of your life is on the line: