Philadelphia Criminal Defense Blog

PA Superior Court: Trial Court May Grant New Trial in Criminal Case Sua Sponte

Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

The Superior Court has decided the case of Commonwealth v. Becher, recognizing that a trial court may grant a new trial to a defendant on its own even after a conviction. The Superior Court, however, reversed the grant of the new trial in this case because the error relied upon by the trial court in granting the new trial was not significant enough to justify such an extreme measure. This case is helpful for the defense in that it reaffirms the ability of the trial judge to grant a new trial when an egregious error has occurred, but it was not good for this defendant as this particular defendant had his grant of a new trial reversed.

The Facts of Commonwealth v. Becher

The defendant, three of his cousins, and a friend went to a strip club. There were members of a motorcycle club at the strip club who started an altercation with an intoxicated person and beat him up outside of the club. One of the defendant’s cousins taunted the club members for beating up an intoxicated person. The cousin and a club member started to fight but were quickly separated. Another cousin entered the club to grab the defendant. He was unaware of any altercations. At that time, the two remaining cousins reinitiated the fight. The defendant emerged from the club, observed the physical altercation, drew his gun, and struck one of the club members with it. The defendant then dropped the gun, and a melee ensued. During the struggle, the defendant was shot, recovered the gun himself, and shot two club members.

The Issue at Trial

At trial, three motorcycle club members testified that during the fight, the defendant’s cousin kept yelling that she was going to get her cousin and have him “smoke” them. After the Commonwealth had witnesses testify to this threat, the defendant's lawyer objected on hearsay grounds to the admission of the cousin’s threats. The trial court overruled the objection. The Commonwealth referred to the cousin's threats in closing arguments, and the trial court gave the jury a cautionary instruction. The trial court instructed the jury not to use the statements against the defendant as proof of his intent.

A jury found the defendant guilty of third-degree murder, finding he did not act in self-defense. The defendant’s lawyer filed a motion for a new trial alleging that the verdict was against the weight of the evidence. At sentencing, the trial court ruled that it would grant the defendant a new trial for a different reason. The trial court found that a new trial was necessary in the interests of justice because the testimony of the cousin’s threats was blatant and inadmissible hearsay. The trial court determined that it should have precluded the threats. Alternatively, if the statements were not hearsay, they were still unfairly prejudicial and should not have been admitted. Therefore, the trial court granted the defendant a new trial sua sponte.

The Appeal

The Commonwealth filed an appeal to the Pennsylvania Superior Court. On appeal, the Commonwealth argued that the trial court abused its discretion in sua sponte granting a new trial to the defendant because none of its reasons supported taking such an extreme measure.

The Superior Court agreed. The Court recognized that a trial court may grant a new trial sua sponte in the interests of justice. The ability to do so, however, is limited. Generally, a court may only do so when there has been some kind of egregious error in the proceedings. Additionally, the standard that must be met depends now whether a party to the proceedings has recognized and preserved the error. When a party recognizes an error but fails to preserve that error, there must be an exceedingly clear error of a constitutional or structural nature. The result must be a manifest injustice that amounts to severely depriving a party's liberty interest. Because the defendant’s attorney was aware of and objected to the threats at some point during the trial, the Superior Court reviewed the grant of a new trial under this higher standard. The lawyer had objected but not moved for a mistrial.

First, the Superior Court rejected the trial court’s conclusion that the threat was blatant, inadmissible hearsay. Instead, the threat had been admitted for a proper purpose. The threat was not used to prove the defendant’s state of mind but instead to tell the whole story of events. Further, a threat to do something is not necessarily a statement offered for the truth of the matter asserted. Instead, it is more of a present sense impression in that it is a statement about what someone intends to do. In this case, the witness intended to have the defendant commit the shooting.

The Superior Court also rejected the trial court’s conclusion that the statement was more prejudicial than probative. The Court found both that the statement was relevant, that it was not unfairly prejudicial, and that the trial court prevented any unfair prejudice by giving the jury a cautionary instruction that it should not hold the statement against the defendant. Therefore, the Court concluded that trial court erred in granting a new trial. The errors cited by the trial court were not actually errors, and even if they were, they were not big enough to justify a sua sponte grant of a new trial.

Therefore, the Superior Court concluded that the trial court abused its discretion in granting the defendant a new trial sua sponte. The Court reversed the trial court's order and remanded it to hear the motion for a new trial based on the weight of the evidence argument. The case obviously does not help this particular defendant, but it does reaffirm that where an error is egregious enough, a court retains the inherent authority to order a new trial in order to fix that error.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

Goldstein Mehta LLC Criminal Defense Attorneys

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

Third Circuit: Pennsylvania State Court Rules on Use of Co-Defendant's Confession Against Defendant Violate Confrontation Clause

Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire - Criminal Defense Lawyer

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has decided the case of Freeman v. Fayette, holding once again that Pennsylvania’s rules regarding the use of redacted statements by co-defendants against the defendant in a criminal case are unconstitutional. The Third Circuit’s decision is not technically binding on the state courts because the Third Circuit only addresses federal appeals. But because the Third Circuit eventually reviews many serious state decisions during federal habeas litigation, particularly in murder cases, the Third Circuit’s ruling could have a dramatic impact on Pennsylvania criminal procedure. In this case, the Third Circuit held once again that where a co-defendant gives a statement which implicates both the defendant and the co-defendant in the crime, redacting the co-defendant’s statement to remove the defendant’s name and replace it with “the other guy” or something similar doe snot adequately protect the defendant’s confrontation clause rights. In this case, the Court retired this point, but it did find that although the defendant’s rights had been violated, the violation amounted to harmless error because the evidence against the defendant was so strong.

The Facts of Freeman v. Fayette

The Commonwealth charged four men with robbery, kidnapping, and murder. One pleaded guilty before trial and agreed to testify against his co-conspirators. Three of the four co-defendants proceeded to trial. During the trial, the court heard testimony from various witnesses placing the four men together around the time of the crime. Finally, the Commonwealth used a statement by one of the remaining three co-defendants implicating the others. That defendant did not testify, and the statement was redacted but still referred to the other co-defendants as “the first guy" and "the second guy." The Commonwealth read the statement to the jury over the objections of the defense attorneys for those defendants. The judge instructed the jury that the statement was to be used only as evidence against the defendant who made the statement, not the co-defendants. The court also repeated this cautionary instruction at the end of the trial. A jury found all three men guilty of second-degree murder. The trial court sentenced them to the mandatory sentence of life without parole.

The Criminal Appeal

On appeal, the Pennsylvania Superior Court affirmed the defendant’s conviction, concluding that there was no Confrontation Clause or Bruton violation. After exhausting his appeals and post-conviction relief at the state level, the defendant filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the federal district court. The district court concluded that the admission of the co-defendant's statement violated the defendant’s confrontation clause rights. The court also concluded that its admission was not harmless error, so the court granted the defendant’s writ of habeas corpus. The Commonwealth then appealed the decision to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals.

What is the Confrontation Clause, and what is a Bruton issue?

The Confrontation Clause, which is part of the Sixth Amendment, provides criminal defendants with the right to confront the witnesses against them. This means they have the right to cross-examine witnesses under oath at trial. In Bruton v. United States, prosecutors tried two defendants together for armed robbery. At trial, prosecutors used one of the defendant’s confessions against him, and the statement also implicated the co-defendant. The judge instructed the jury only to use the statement against the defendant, not the co-defendant. A jury convicted both men for the crimes charged. The Supreme Court ruled that the trial court violated the co-defendant’s right to confront and cross-examine despite the jury instruction because the trial court’s ruling essentially allowed the person who confessed to implicate the defendant without that person’s statement being subject to cross-examination.. Subsequent United States Supreme Court decisions have also held that redactions may not be sufficient unless they eliminate both the defendant's name and any reference to their existence. The state courts, however, have often allowed the Commonwealth to simply replace the defendant’s name with something generic like “the other guy.”

The Third Circuit’s Decision

Because the Commonwealth’s appeal challenged the district court’s ruling in habeas litigation, the Third Circuit was required to use a very deferential standard of review. Under the AEDPA, the mere fact that the state court was wrong is not enough to obtain relief. Instead, a court must first 1) determine whether there has been an error (in this case a Bruton violation), and then 2) determine whether the state court made a determination that was contrary to or an unreasonable application of clearly established federal law. A defendant must then also show prejudice. It is enough to show the trial judge was wrong; instead, the defendant must show that the trial judge was very, very wrong and that it likely affected the outcome of the proceedings.

Here, the Commonwealth argued that using "the first guy" and "the second guy" did not facially incriminate the defendant because these substitutes did not refer to him by name. The Commonwealth therefore argued that the statement did not facially incriminate the defendant and that any incrimination effect could come only inferentially. The Superior Court, however, has held that Bruton violates generally do not occur when a statement has been redacted and any incriminating effect arises inferentially.

The defendant argued that the redactions left it so obvious who the co-defendant was talking about that they offered insufficient protection, essentially making the statement directly accusatory. It named two perpetrators and left the two perpetrators unnamed, referring to them as "the first guy" and "the second guy." This made it so that the jury only needed to look up at the defense table and see the two co-defendants to identify who the statement implicated. Accordingly, the Third Circuit rejected the conclusions of the state courts that the statement did not violate Bruton. The Court had made similar rulings on numerous occasions, to the Court also found that the state courts clearly failed to apply federal law. Unfortunately, the Court also found that the evidence against the defendant was overwhelming and that he would have been convicted even without the statement, so the Court reversed the district court’s order granting the writ of habeas corpus. The defendant will therefore not receive a new trial despite the obvious violation.

Given the Third Circuit’s ruling, the case is not helpful for the individual defendant in this case. It is, however, very helpful for criminal defendants going forward as it once again sends a message to the state courts and Commonwealth that inadequate redactions do not render a co-defendant’s statement admissible against the defendant unless the defendant has a chance to cross-examine the co-defendant.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

Goldstein Mehta LLC Criminal Defense Attorneys

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

Federal Sentencing Update: United States Sentencing Commission Proposes Limiting Use of Acquitted Conduct at Sentencing

Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

The United States Sentencing Commission recently proposed a major change to federal sentencing law, indicating that it may bar the use of acquitted conduct at sentencing where defendants have been acquitted of some charges but convicted of others. This would represent a major change in federal sentencing law. Currently, federal judges may sentence criminal defendants based on conduct for which the jury acquitted them. This is an incredibly unfair practice as it means that a defendant may go to trial on two charges, get acquitted by the jury of the more serious charge when the jury finds that the government could not prove the offense beyond a reasonable doubt, and then still be sentenced as if they had been convicted of the more serious charge.

Acquitted conduct is an offense for which the defendant was not convicted. For example, in many cases, defendant could be charged with guns and drugs at the same time. The penalties for federal drug offenses can be draconian on their own, but the presence or use of a firearm during the commission of the drug offense can result in mandatory minimums and federal sentencing guidelines that are exponentially higher. Federal judges take the guidelines incredibly seriously, so the guideline calculation is extremely important. Currently, there is nothing preventing federal judges from treating a defendant who has been convicted of a drug offense but acquitted of the firearm offense the same at sentencing as if the defendant had been convicted of both offenses. This can lead to a drastically longer sentence even though the jury partially acquitted. Federal judges also may often consider conduct for which the defendant was never charged.

Similar sentencing issues can arise in white collar cases, as well. For example, where a jury acquits a defendant of some counts related to a fraud scheme but convicts on others, the judge can currently sentence based on dollar amounts involved in the counts for which the defendant was acquitted. Because the loss amount involved is often the most important factor in the federal sentencing guideline calculation, this can have a significant impact on the resulting sentence.

Numerous defendants have attempted to challenge this practice as violating the Constitution in the United States Supreme Court, but the Supreme Court has rejected those challenges. The Supreme Court concluded in United States v. Watts that “a jury's verdict of acquittal does not prevent the sentencing court from considering conduct underlying the acquitted charge.” Some of the recently confirmed justices have previously signaled that they may reconsider that ruling, but so far, the Court has not accepted any petitions for certiorari on the issue.

The Sentencing Commission, however, could avoid the need for court action should it approve the proposed change. The proposed change would preclude courts from being able to consider acquitted conduct at sentenicng. The Sentencing Commission was created by Congress for the purpose of establishing the rules by which the guidelines are calculated. Ultimately, the guidelines produce a recommended sentencing range for the judge to consider when imposing sentencing. Until recently, the guideline range was actually mandatory and a judge could not sentence below the guidelines under most circumstances. The guidelines are no longer mandatory, but they are still extremely important.

The downside of the change being approved by the Sentencing Commission rather than the Court is that the change would almost certainly not be retroactive. However, this is an important change that strengthens the presumption of innocence and holds the government to its burden of proving a defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Criminal defendants should not be sentenced for things that the jury found that they did not do.

This change would only affect federal sentencing proceedings. It would not alter the current practice in the Pennsylvania state courts. The Pennsylvania state courts also use sentencing guidelines, but the guidelines are not quite as important as they are in federal court. The state courts are far more likely to depart from them. Further, it is relatively rare for courts to consider acquitted conduct or conduct for which a defendant was not charged in a state court sentencing proceeding. It is not necessarily prohibited at all times, but state court judges almost always agree that they should not hold alleged offenses for which a defendant was acquitted against them.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

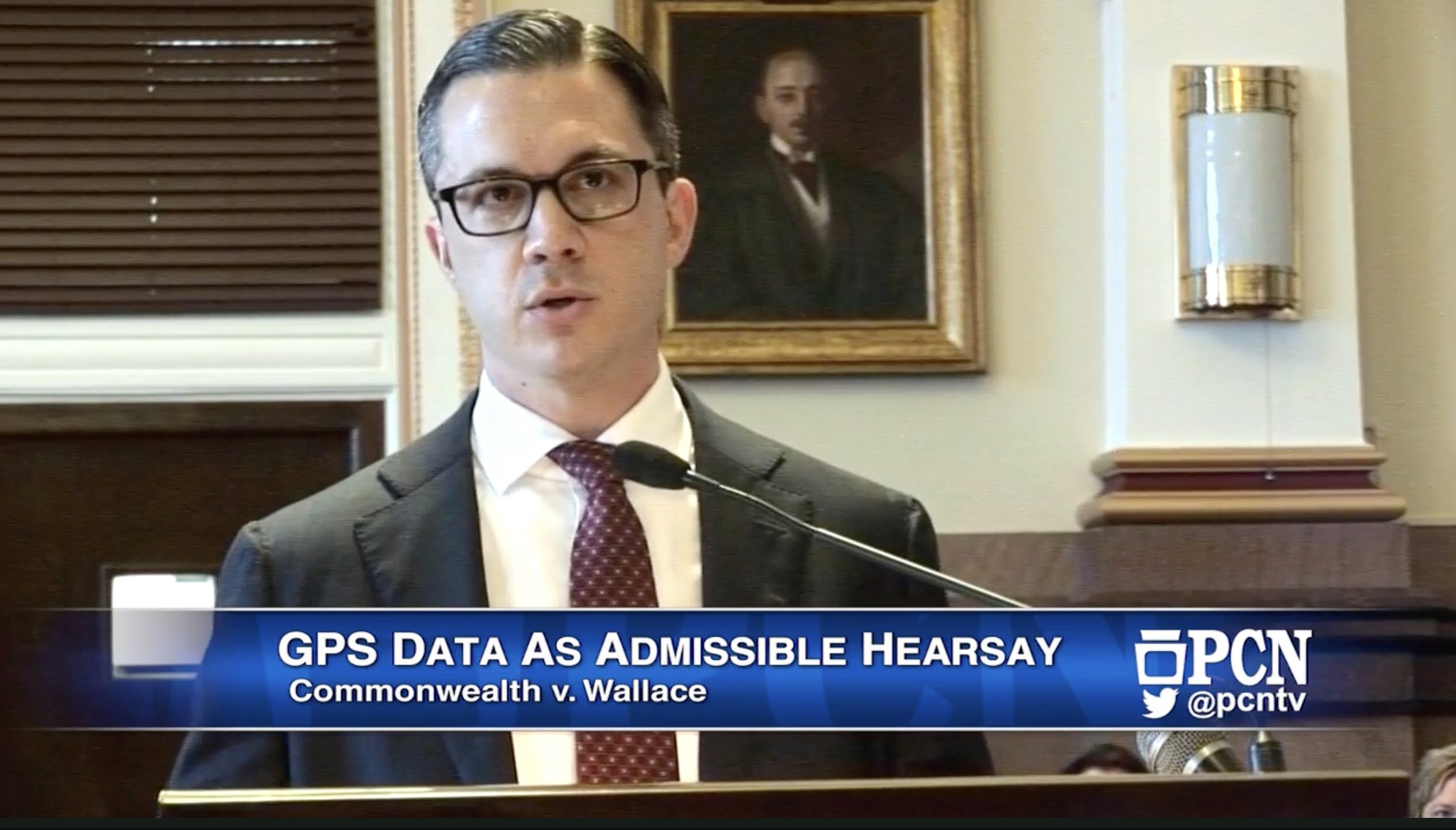

Federal Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire, at oral argument

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

PA Superior Court: Trial Court Must Hold Ability to Pay Hearing Before Finding Parolee in Violation

The Pennsylvania Superior Court has decided the case of Commonwealth v. Reed, finding that the trial court erred in sentencing the defendant to prison for violating parole by failing to pay costs and fines without first holding a hearing to make sure that the defendant was actually able to make those payments. Courts may sentence a defendant to prison for failing to pay restitution, court costs and fines, but they can only do that where the failure to pay is willful. Therefore, a court must first hold a hearing to determine whether or not a defendant can afford to pay before sentencing a defendant to jail.

The Facts of Reed

The defendant was given a sentence of six months to two years, minus a day, of incarceration. In addition, he was ordered to refrain from illicit drug use, pay fines and costs, complete a drug and alcohol evaluation and treatment, and report to probation. About six months later, the court granted parole. Then, 16 months later, the defendant received notice that he had allegedly violated his parole.

The defendant appeared for a violation of probation (VOP) hearing. The trial court found the defendant violated his parole by (1) using illicit drugs, (2) failing to pay court-ordered fines and costs, (3) failing to submit to a drug and alcohol evaluation, and (4) failing to report to his parole officer. The court revoked the defendant’s parole and sentenced him to his back time. Back time is the time during which the defendant would have been on parole had he not violated.

The Issues on Appeal

On appeal, the defendant raised three issues. First, he challenged the adequacy of the notice of the parole violation. The defendant argued that the notice sent to him through the mail did not adequately inform him of all the details of the alleged parole violation. The Superior Court found this issue waived because the defendant had not brought it up in the trial court.

Second, the defendant argued that the conditions of parole which he was accused of violating had not actually been made a part of his sentence, and he could not violate something which was not part of his sentence. The Superior Court rejected this challenge, finding that paying fines and costs, submitting to drug assessments, refraining from the use of illegal drugs, and reporting were all part of the defendant’s sentence.

Finally, the defendant argued that the trial court erred in violating him for failure to pay costs and fines without first holding an ability to pay hearing. The Superior Court cited Pennsylvania Rule of Criminal Procedure 706(A). The rule provides:

A court shall not commit the defendant to prison for failure to pay a fine or costs unless it appears after hearing that the defendant is financially able to pay the fine or costs.

The Superior Court further cited Commonwealth v. Cooper, recognizing that when a defendant is found in violation of their parole and recommitted, if failure to pay was part of the violation, then the defendant is entitled to an ability to pay hearing. Here, the Superior Court found there was an error by the trial court.

The Superior Court’s Ruling

The Superior Court ruled that even though the trial court properly found violations of parole and sentenced the defendant based on those violations, the trial court was required to hold an ability to pay hearing before ordering any sentence of incarceration. The trial court erred in failing to give the defendant the opportunity to establish his inability to pay his costs and fines prior to imposing an incarceration sentence. Therefore, the court vacated the sentence and remanded the case for an ability to pay hearing and re-sentencing.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

Goldstein Mehta LLC Criminal Defense Lawyers in Philadelphia

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.