Philadelphia Criminal Defense Blog

The New 2024 Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines

Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

A major update to the Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines went into effect on January 1, 2024. The new guidelines significantly revamp Pennsylvania’s system for sentencing defendants following a conviction at trial or guilty plea. The guidelines had largely been handled the same way since their creation, but now, the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing has significantly changed the way prior record scores are calculated and created a very different sentencing matrix. The old guidelines still apply to offenses committed before 2024. The new 8th edition of the guidelines apply for offenses committed on or after January 1, 2024.

What are the sentencing guidelines?

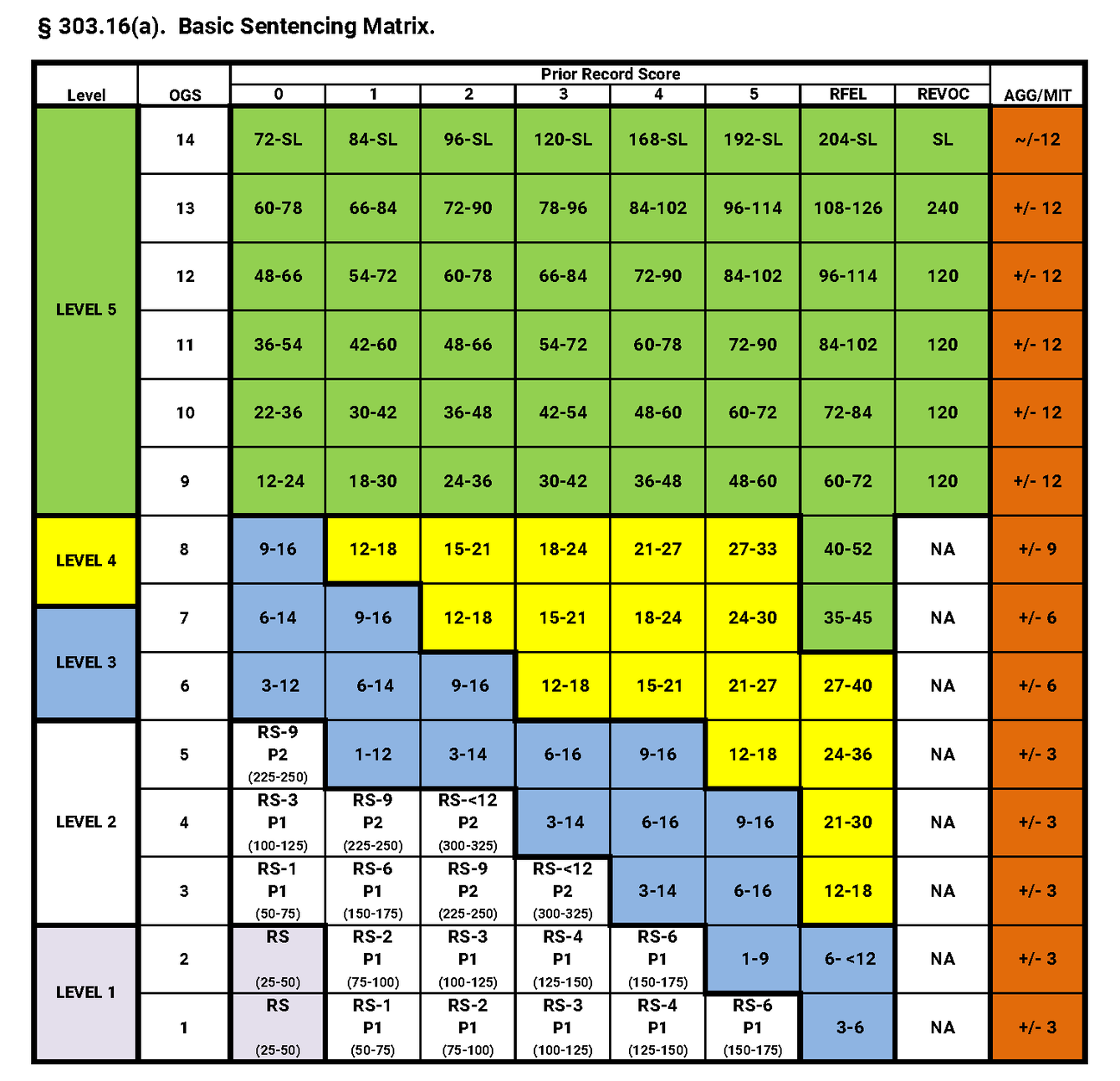

As an introductory reminder, prior to sentencing a defendant in Pennsylvania state court, a judge must calculate the guidelines for the offense. Every offense has an offense gravity score, and every defendant has a prior record score. The judge must correctly determine the offense gravity score (OGS) and the defendant’s prior record score (PRS). Where those two numbers meet on the sentencing guidelines matrix then provides the judge with a recommended range for the minimum sentence. With the exception of very short sentences (like 30 days in jail for possession of marijuana), every sentence in Pennsylvania must have a minimum and a maximum. The maximum must be at least double the minimum in order for the sentence to be legal.

Under Pennsylvania’s guidelines system, the judge must correctly calculate the sentencing guidelines and then consider sentencing the defendant within the range provided by the guidelines for the defendant’s minimum sentence. Ultimately, the judge does not have to sentence the defendant within the guidelines. The judge could decide there is something less serious about the case and go below the guidelines or something more serious about the case and go above the guidelines. Guideline sentences, however, are very difficult to appeal. It is generally easier to appeal a sentence when the judge departs from the guidelines.

The basic idea of the new guidelines is the same; every offense will have guidelines based on an offense gravity score and a prior record score. Calculating those numbers, however, has become a little bit more complicated.

The Offense Gravity Score

The offense gravity score is relatively easy to determine. The Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing provides a list of offenses, and each offense has a numerical offense gravity score that goes with it. First, the defense attorney must determine the offense gravity score for each offense charged by reviewing the list of offenses in the complaint or bills of information. It is important to look at the specific subsection charged as different subsections may have different offense gravity scores.

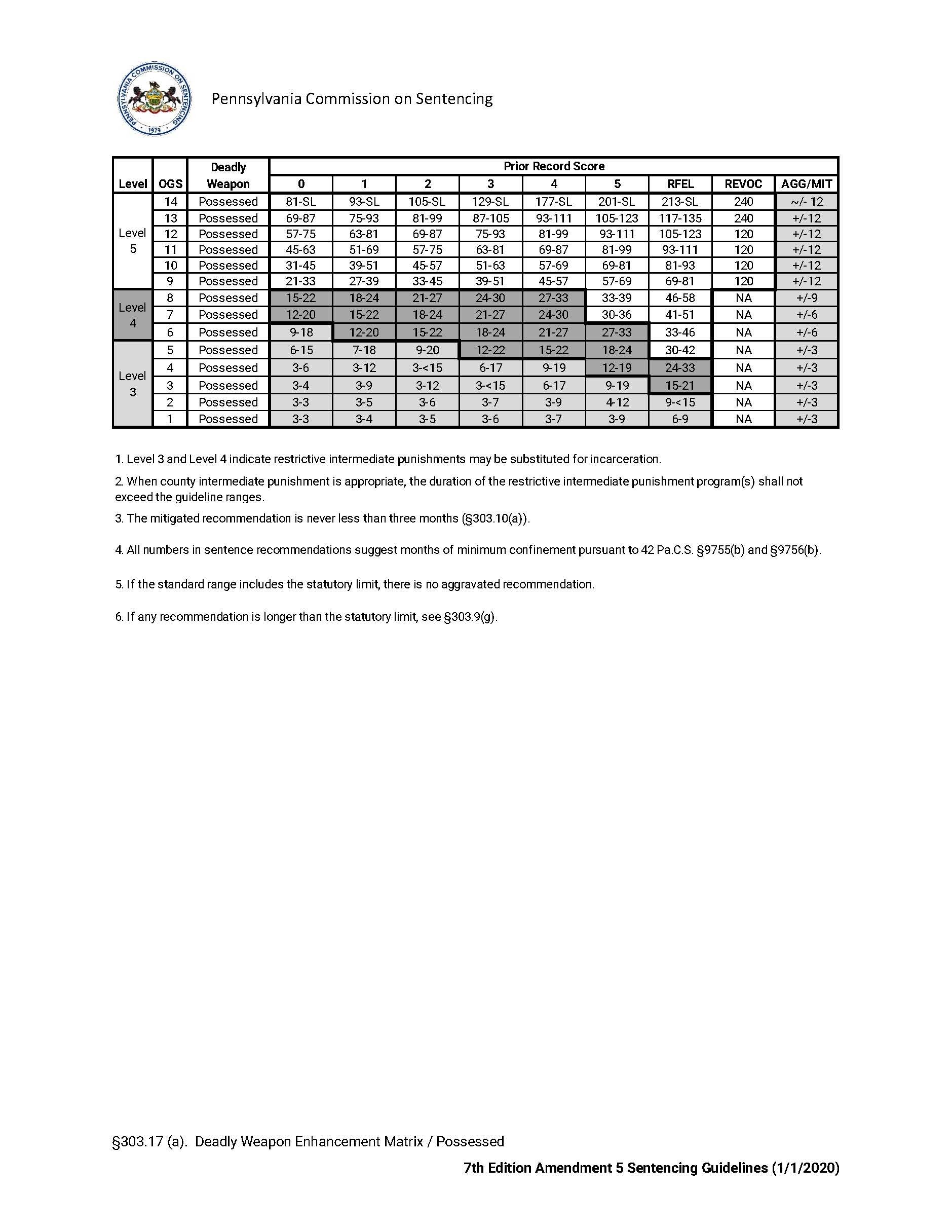

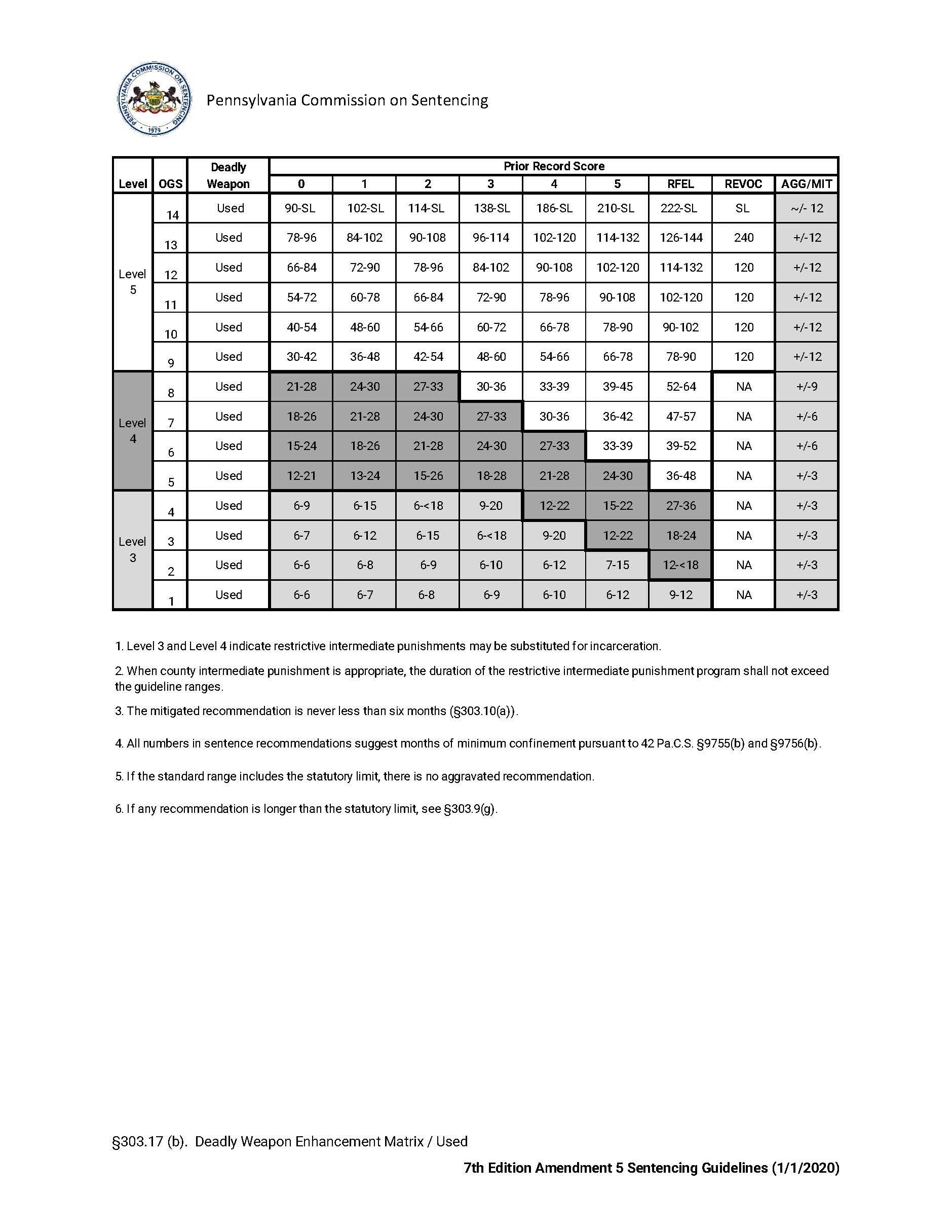

Second, the attorney must determine whether any enhancements apply. The two most common enhancements are the deadly weapon possessed and the deadly weapon used enhancements. They apply when a deadly weapon like a gun or a knife was either used or possessed during the commission of the crime.

If a deadly weapon was possessed but not used, then the offense gravity score will be two points higher.

If the deadly weapon was used, then the offense gravity score will be three points higher.

The deadly weapon enhancements do not apply if the statute itself always involves the use of a deadly weapon because the use of a deadly weapon is an element of the offense. Possessing an instrument of crime, prohibited offensive weapons, possession of a weapon on school property, assault with a deadly weapon, and violations of the uniform firearms act do not require the application of the deadly weapon enhancements because the possession or use of a deadly weapon is part of the offense.

There are three other enhancements which are less likely to apply.

First, there is a school zone enhancement. If a controlled substance was delivered or possessed with the intent to deliver in a school zone, then there is a one point addition to the offense gravity score.

Second, there is a criminal gang enhancement of two points.

Third, there is a domestic violence enhancement of two points. If the defendant committed the offense against a family or household member, then the enhancement may apply.

It is important to accurately calculate the offense gravity score. Further, the calculation of the correct offense gravity score may be subject to litigation. If the Commonwealth alleges that a particular object was a deadly weapon but the object was not a gun or a knife, it may be possible to argue that the object was not actually a deadly weapon.

The defense should carefully review the pre-sentence investigation and calculation of the guidelines and object if the guidelines seem too high or are based on allegations the Commonwealth may not be able to prove. It is important to remember that the Commonwealth bears the burden of establishing that an enhancement applies by a preponderance of the evidence. It is not necessarily the defense attorney’s job to prove that it does not apply. The Commonwealth, however, may use circumstantial evidence in order to meet this burden.

The Prior Record Score

Second, the defense attorney must properly calculate a defendant’s prior record score. The system for determining the offense gravity score did not change significantly with the enactment of the new guidelines, but dealing with the prior record score is very different. Instead of looking at each charge for which a defendant has been convicted and assigning points to that charge and then adding those points up, the prior record score will now be based on the most serious offense of conviction for each case where a defendant was convicted of a crime.

There are four categories of offenses.

First, there are misdemeanors which have not been designated as serious crimes (POG1 offenses).

Second, there are third degree felonies and unclassified felonies (like possession with the intent to deliver) which have not been designated as serious crimes (POG2 offenses).

Third, there are serious crimes, first-degree felonies, and second-degree felonies (POG3 offenses). VUFA offenses and SORNA offenses are generally considered serious crimes that fall within the third category.

Fourth, there are crimes of violence which would otherwise be considered strike offenses (POG4 offenses). These include offenses like first-degree felony aggravated assault, attempted murder, rape, IDSI, and certain robberies and burglaries. There are other offenses which fall within this list. They are defined in 42 Pa.C.S. § 9714(g).

In calculating the prior record score, the defense attorney must determine which prior offense on the defendant’s record is the most serious. The attorney should then determine how many offenses of the same seriousness fro which the defendant has been convicted. The number of offenses for which the defendant has been convicted of the same seriousness will then determine the defendant’s prior record score based on where that number falls on this chart.

The Prior Record Score Matrix

For example, using the above chart, a defendant with two misdemeanors (which go under the POG1 category) will fall under prior record score one.

A defendant with two F1 robberies (which are crimes of violence that fall under POG4) will have the highest prior record score of four.

A defendant with three prior possession with the intent to deliver cases, which fall under POG2, will fall under prior record score three.

A defendant with two VUFA convictions (POG3), would have a prior record score of three.

Lapsing of Convictions for the Prior Record Score

Under the old guidelines, convictions were permanent. Even if a defendant was convicted of an offense fifty years ago, the offense would still count towards the defendant’s prior record score unless the offense was a juvenile adjudication and a certain amount of time had passed in between the adjudication and new offense. Now, convictions will no longer count if a defendant goes a certain amount of time in between arrests.

Juvenile Adjudications

First, juvenile adjudications lapse relatively quickly.

Juvenile adjudications for POG1 offenses (mostly misdemeanors) do not count towards the prior record score.

Juvenile offenses in POG2 (mostly third-degree felonies and PWIDs) do not count once the defendant turns 25.

POG3 offenses (felony ones and felony twos that are not crimes of violence) do not count if the defendant is “crime-free” for ten years.

Finally, POG4 adjudications (crimes of violence) do not count after 10 years crime-free if they were committed when the defendant was between 14 and 16 or after 15 years crime-free if the defendant was 16 or older.

Adult Convictions

Under the old guidelines, adult convictions counted forever. Now they may lapse after a certain amount of time.

POG1 offenses lapse after ten years from the conviction date even if the defendant was not crime-free.

POG2 and POG3 offenses lapse after 15 years of being crime-free.

POG4 offenses lapse after 25 years of being crime-free.

The time period for being crime-free runs either from the date of release from incarceration or the date of the sentence if the defendant received probation.

Again, if there is a dispute, the Commonwealth bears the burden of proving that lapse should not occur.

The following is the definition of a crime-free period:

‘‘Crime-free period.’’ Following a conviction and sentence and subsequent release to the community, the completion of a prescribed period of time without commission of a new felony or misdemeanor, for which the person pleads guilty or nolo contendere or is found guilty. For non-confinement sentences, release to the community begins on the date of sentencing; for confinement sentences, release to the community begins on the date of initial release on parole, or release following completion of the confinement sentence, whichever is earlier.

The New 2024 Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines Matrix

Once the criminal defense attorney has calculated the offense gravity score and prior record score, the next step is to see where those numbers meet on the below matrix. That number then provides a recommended minimum sentence for the judge to consider. The judge may go higher or may go lower, but the judge must properly calculate the guidelines and consider them. The judge must put the guidelines on the record, and if the judge decides to go above or below the guidelines in sentencing the defendant, the judge must announce the reasons for the departure on the record at the time of sentencing. The failure to properly calculate the guidelines or put the reasons for a departure on the record could be the basis for a successful appeal.

The New 2024 Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines Matrix (8th Edition)

A Judge May Depart From the Guidelines

Finally, a judge may depart from the guidelines. Judges may consider the following factors when deciding whether to depart:

(i) Nature and circumstances of the offense:

(A) Neither caused nor threatened serious harm.

(B) Conduct substantially influenced by another person.

(C) Acted under strong provocation.

(D) Substantial grounds to justify conduct.

(E) Role in offense.

(F) Purity of controlled substance.

(G) Abuse of position of trust.

(H) Vulnerability of victim.

(I) Temporal pattern.

(J) Offense pattern.

(K) Multiple offenses in a criminal incident.

(ii) History and character of the person:

(A) No history of criminal conduct.

(B) Substantial period of law-abiding behavior.

(C) Circumstances unlikely to recur.

(D) Likely to respond affirmatively to probation.

(E) Imprisonment would entail excessive hardship.

(F) Accepts responsibility.

(G) Provides substantial assistance.

(H) Compensated victim or community.

(I) Character and attitude.

(J) Treatment for substance abuse, behavioral health issues, or developmental disorders or disability.

(2) Unless otherwise prohibited by statute, the consideration of validated assessments of risk, needs and responsivity, or clinical evaluations may be considered to guide decisions related to the intensity of intervention, use of restrictive conditions, and duration of community supervision.

(3) Adequacy of the prior record score. The court may consider at sentencing prior convictions, juvenile adjudications, or dispositions not counted in the calculation of the PRS, in addition to other factors deemed appropriate by the court.

Obviously, this is a big list of reasons for a potential departure. At the end of the day, it is important to remember that the new guidelines, like the old ones, are not mandatory minimums. They provide the judge with a starting point for the potential sentence. In some counties, the guidelines are treated almost as mandatory minimums and it is rare to see judges go below or above the guidelines. In others, the guidelines are routinely calculated but then ignored. Additionally, the guidelines do not tell the judge whether to impose consecutive or concurrent sentences for different offenses. It is also not clear yet whether separate cases which were consolidated and disposed of at the same time will count as one case or two cases for calculating the prior record score, so some of these things will still be subject to litigation. Either way, it is important to correctly calculate the guidelines as they will give the defendant an idea of what they are facing if they are convicted and the improper calculation of the guidelines at sentencing could be the basis for an appeal or PCRA claim.

Facing criminal charges or appealing a criminal case in Pennsylvania? We can help.

Philadelphia Criminal Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court, including the exoneration of a client who spent 33 years in prison for a murder he did not commit. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

United States Sentencing Commission Votes to Eliminate Status Points

Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

The United States Sentencing Commission has voted both to eliminate status points for most federal criminal defendants under the federal sentencing guidelines as well as to make that change retroactive. Until recently, the Sentencing Commission had not had a quorum of commissioners since 2018, so the Commission had been unable to propose changes to the federal sentencing guidelines. Now that a quorum of commissioners has been appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, the Sentencing Commission is once again able to enact changes to the guidelines. Generally, the changes which receive a majority vote from the commissioners go into effect unless overturned by Congress within a 180 day review period.

What are status points?

Under the current federal sentencing guidelines, each defendant that is found guilty by a judge or jury or who pleads guilty receives an Offense Level and a Criminal History Score. The offense level is based on the seriousness of the offense. Offenses typically have a base offense level for the offense of conviction, and then there are all sorts of potential enhancements that may apply depending on the way in which the offense was committed.

For example, a wire fraud conviction would have a certain base offense level, but then the offense level would increase based on the amount of money lost by the victims of the fraud as well as other potential factors such as whether the defendant used sophisticated means to commit the fraud or had a leadership role in the scheme. Other enhancements may potentially apply in any given case.

During the pre-sentence report process, each defendant will also then be assigned a criminal history category based on their criminal history points by the United States Probation Officer who prepares the pre-sentence report. The criminal history category is generally based on the number and type of convictions that the defendant has previously received as well as the length of any sentences served for those convictions.

The sentencing guidelines, which provide a recommended sentence in months that the judge must consider imposing, are then calculated based on where the offense level and criminal history category meet. This chart shows the recommended sentencing range for each offense level and criminal history category.

Federal Sentencing Guidelines Matrix

The judge is not required to impose a guideline sentence, but judges take the guidelines extremely seriously.

Under current law, most offenders who are under probation, parole, or federal supervised release supervision at the time of the commission of the new offense receive two additional points towards their criminal history category for being under supervision at the time of the offense. Two points can often be the difference between specific criminal history categories, resulting in much higher guidelines for a defendant who is under supervision than one who is not. This can have a big impact on the recommended sentencing range.

For example, a defendant with an offense level of 34 and a criminal history category of II would be facing sentencing guidelines of 168 - 210 months’ incarceration. If the individual was under supervision at the time of the offense, the criminal history category could be increased to category III, and then the defendant would instead be facing 188 - 235 months’ incarceration. This means the defendant could receive an additional two years at the high end of the guidelines, so the difference can be significant.

Now, the federal Sentencing Commission has voted to eliminate status points for most defendants. Specifically, the Sentencing Commission abolished all status points for people who had fewer than seven accumulated criminal history points driving their criminal history category. For those with seven or more points, only one status point would be added rather than two. In making this change, the commission determined that status points had little to no relevance in the accurate determination of a criminal history profile.

Will the change to status points under the federal sentencing guidelines be retroactive?

On August 24, 2023, the Sentencing Commission also voted to make the change retroactive and to allow inmates who would be affected by the change to file motions to reduce their sentences starting in February 1, 2024. Defendants may not file motions to reduce their sentences before that date, but if a defendant received status points that affected their guideline range, the they may petition the district court for a reduction in sentence based on the retroactive change in the sentencing guidelines. This change also assumes that Congress does not vote to overturn the proposed amendment to the guidelines.

Ultimately, the Sentencing Commission determined that status points do very little to predict whether a particular defendant is likely to re-offend. Therefore, whether or not someone was under supervision at the time of the offense should no longer be factored into the guideline calculation going forward.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

Goldstein Mehta LLC Criminal Defense Lawyers

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.

PA Sentencing Guidelines | I got arrested. Am I going to jail?

The PA Sentencing Guidelines provide the sentencing judge with a range of minimum sentences to consider imposing following a conviction.

The Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines

Note: This article is based on the pre-January 1, 2024 guidelines. Any offense committed prior to January 1, 2024 will involve the guidelines discussed in this article. For a discussion of the new guidelines, please see this article.

One of the most common questions we get when meeting with a new client is, “What am I looking at if we lose? Am I going to go to jail?” The answer is almost always, “it depends.”

First, if the client has made the smart decision and hired one of our PA criminal defense attorneys, the client could very well be looking at winning the case or negotiating entry into a pre-trial diversionary program that will not result in a conviction or incarceration. The above question assumes that the client is going to lose and be convicted of the most serious charge, which is often not the case. There are many cases that can be won at preliminary hearing, through pre-trial motions, or at trial. Each case is different, but we regularly try and win cases. Even those cases that cannot be won can often be negotiated down to lesser charges, so even when the prosecution's evidence is strong, there is always the possibility of working out a good deal for the defendant. Therefore, there are lots of cases in which the client will ultimately not end up serving any kind of sentence or will eventually face a sentence on a less serious charge.

Second, although there are never any guarantees, it is usually possible to predict the best and worst case scenario by considering any applicable mandatory minimums, sentencing guidelines, and the sentencing practices of the judge. Even though it is never possible to predict an outcome or whether a defendant could go to jail with complete certainty, it is generally possible to have an idea of what the possible and most likely outcomes are for different types of charges.

Pennsylvania Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Laws

When considering what sentence you could get, the first place to start is to find out whether there are any mandatory minimums. Most Pennsylvania mandatory minimum sentences were eliminated by decisions of the United States and Pennsylvania Supreme Courts. However, a handful of mandatory minimums remain.

For example, there are still mandatory minimums for repeat offenders who are convicted of certain crimes of violence such as F1 Robbery, Aggravated Assault, Homicide, certain types of Burglary and Sex Crimes, and other serious “strike” crimes. There are also significant mandatory minimum sentences for DUI/DWI. Other mandatory minimums which apply to the sexual abuse or physical assault of children have also been reinstated and may call for significant periods of incarceration.

The Pennsylvania state legislature has considered reinstating the other mandatory minimums which were struck down by the courts such as those based on drug weights and gun possession while committing a crime of violence, but it has not yet done so. You can learn more about mandatory sentences here. There are also still a number of significant mandatory minimums for many federal charges. Therefore, the first step is to figure out if there are any mandatory minimums. If there is one, then the strategy will likely become avoiding a conviction for the charge or fact that would trigger the mandatory minimum. Any mandatory minimum will trump the sentencing guidelines, meaning that if the mandatory minimum is higher than the guideline range, the court must still sentence to the longer sentence called for by the mandatory minimum.

Calculating the Sentencing Guidelines in Pennsylvania

Second, once you and your defense attorney have determined whether there are any mandatory minimums which could apply to the offense, it is critical to calculate the Pennsylvania sentencing guidelines. The guidelines provide a good estimate of what type of sentence the defendant could receive if convicted. In both Pennsylvania and the federal system, the sentencing guidelines are not mandatory, meaning a judge can depart upward or downward from the guidelines if there is a good reason to do so. However, judges in both systems are required to correctly calculate the guidelines, strongly consider them, and provide sufficient reasons on the record for departing from them if they choose to do so. Departures from the guidelines are generally more common in state court than they are in federal court, but even in state court, the judges typically sentence based on the guidelines. In recent years, the guidelines have become less important in Philadelphia, but the judges must still calculate them accurately and consider them.

Under the Pennsylvania system, every sentence (except for extremely short sentences of a month or two) must have a minimum and a maximum. The maximum must always be at least double the minimum. If the maximum is two years or more, then the defendant will typically serve the sentence in a state prison. If the maximum is less than two years, then the defendant will serve the sentence in the county prison. There are some exceptions to this general rule for sentences under five years, particularly in cases involving Driving under the Influence. In those cases, the Commonwealth may agree to allow a defendant to serve even a two-year sentence in the county jail so long as the maximum is no greater than five years.

The Pennsylvania sentencing guidelines provide a recommended range for the minimum sentence. Once the judge picks a minimum, the judge is free to pick whatever maximum the judge feels is appropriate up to the statutory maximum for the offense. The recommended minimum range is calculated by determining the defendant’s Prior Record Score and the Offense Gravity Score of the charge. The Prior Record Score and Offense Gravity Score are then entered into a sentencing matrix, and the matrix provides a recommended minimum sentence. In many cases, the standard sentencing matrix will apply. However, if the prosecution can prove that the defendant possessed or used a deadly weapon during the commission of the crime, then an alternative matrix could apply which will recommend a more severe sentence.

The Offense Gravity Score

Each offense has an assigned numeric Offense Gravity Score. When the judge or pre-sentence investigator calculates the guidelines after a conviction or plea,they will do it for each offense. The judge will typically sentence based on the most serious charge, but a judge can always run sentences consecutively if the judge so chooses. It is often common to attach probation sentences to some of the less serious charges. For purposes of providing an example, possessing a concealed, loaded firearm without a license (which violates VUFA § 6106) carries an Offense Gravity Score of 9. The Offense Gravity Score for each offense can be found at http://www.pacode.com/secure/data/204/chapter303/s303.15.html.

Calculating the Prior Record Score

Once the Offense Gravity Score has been calculated, the next step is to determine the defendant’s Prior Record Score. Just as each charge has a corresponding Offense Gravity Score, each conviction also has a corresponding Prior Record Score. For example, Possession with the Intent to Deliver adds two points towards a defendant’s Prior Record Score. The Prior Record Score is calculated by adding up the points that correspond with each of the defendant’s prior convictions. The maximum Prior Record Score is 5, but there are two special categories for defendants with certain felony convictions. Defendants with prior convictions for F1 or F2 felonies which total more than 5 points have a prior record score of REFEL, and defendants with prior violent convictions for certain F1 felonies who are charged with additional violent offenses could have a prior record score of REVOC. It is also important to note that many adjudications of delinquency for juvenile offenders will count towards the Prior Record Score, but some will not. Many people mistakenly believe that juvenile records do not count in adult court, but depending on the offense and the defendant’s age at the time of the offense, the juvenile record may count towards the Prior Record Score. Even if it does not formally count, a judge will often be made aware of the conviction and will be free to consider it in deciding on as sentence. The Prior Record Score points for each offense are listed at http://www.pacode.com/secure/data/204/chapter303/s303.15.html.

The PA Sentencing Guidelines Matrix (Basic)

The Pennsylvania Sentencing Guidelines Matrix (Standard Range)

Sentencing Guidelines for Possessing a Concealed Firearm Without a License to Carry

Once the Offense Gravity Score and Prior Record Score have been calculated, the above sentencing matrix or chart can be used to determine the recommended minimum sentencing range. There are different matrices for crimes committed while in possession of a deadly weapon or where a deadly weapon was used, and there are also certain sentencing enhancements for certain offenses like possession of child pornography. However, the basic sentencing matrix above applies to most cases. As you can see, in the example above in which a defendant has a Prior Record Score of 2 for a PWID conviction and an Offense Gravity Score of 9 for a VUFA § 6106 charge, the recommended minimum sentence is 24 – 36 months plus or minus 12 months. This means a standard guideline sentence would have a minimum of somewhere between two and three years, but the judge can subtract 12 months if there is strong mitigation evidence or add 12 months if there are significant aggravating factors. The judge would then have to pick a maximum sentence which is at least double the minimum, so if the judge were to sentence the defendant to a minimum of 18 months of incarceration, the judge would have to make the sentence at least 18-36 months.

This leads to the last and possibly most important part of predicting what the defendant is looking at. As the example above illustrates, the judge has a tremendous amount of discretion in determining the sentence. For a VUFA 6106 conviction for a defendant with no record, which is an extremely common situation, the judge could sentence anywhere from probation to 3-6 years in state prison and still have imposed a guideline sentence.

It is very difficult to challenge a guideline sentence on appeal. The Superior Court is often reluctant to even review an above-guideline sentence. For this reason, it is extremely important to have a lawyer who understands not only the mandatory minimums and the applicable sentencing guidelines, but also the sentencing practices of the judge. If the lawyer knows from experience that the judge is likely to impose a mitigated sentence for an open (meaning non-negotiated) guilty plea, then the lawyer can advise a client to reject an offer from the Commonwealth which is not fully mitigated. Likewise, if the lawyer knows that the judge is likely to impose a low guideline sentence even after conviction at a bench trial, the lawyer may be able to provide advice that it is better to have a judge trial than a jury trial. Obviously, it is critically important that you hire a lawyer who knows the system, knows the law around sentencing, and has experience practicing before the judges who would ultimately impose sentence. It is even more important that you have a lawyer who understands the importance of sentencing and how to craft a persuasive mitigation argument for the judge in order to get the judge to impose a mitigated or below guideline sentence.

What factors does a judge consider at sentencing?

There are a number of different factors that a judge could consider at sentencing. For example, the judge will typically look at some of the following factors:

the seriousness of the offense,

whether the defendant has a prior criminal record,

whether the defendant has complied with the conditions of pre-trial release or participated in programs while in custody awaiting sentencing,

whether the defendant has a job,

and whether the defendant has community support and people who are willing to speak on his or her behalf.

A judge would also be required to consider any potential mandatory minimum sentence that could apply.

In order to obtain the best possible sentence for our clients, we often focus on obtaining proof of employment, character letters from friends, family, and community members, and proof of drug or alcohol treatment or other counseling as necessary. In some cases, it can be helpful to obtain an evaluation from a medical profession in order to prepare an expert report as to whether a defendant is likely to respond well to treatment.

Our Philadelphia Criminal Lawyers Can Help

Philadelphia Criminal Defense Attorneys

The Philadelphia Criminal Defense Lawyers of Goldstein Mehta LLC have the legal expertise and practical experience necessarily to properly advise and defend anyone facing criminal charges in Philadelphia and the surrounding counties. We know the law, we know the defenses, and we have experience practicing before the judges. We can evaluate your case and potential defenses and come up with a plan to minimize the consequences of an arrest – whether that means negotiating a better sentence or taking the case to trial for an acquittal. If you or a loved one are facing criminal charges, call 267-225-2545 today for a free, confidential consultation.

PA Sentencing Matrix (Deadly Weapon Possessed)

The Pennsylvania Deadly Weapon Possessed Guideline Matrix

PA Sentencing Matrix (Deadly Weapon Used)

The Pennsylvania Deadly Weapon Used Guideline Matrix

Federal Sentencing Update: United States Sentencing Commission Proposes Limiting Use of Acquitted Conduct at Sentencing

Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire

The United States Sentencing Commission recently proposed a major change to federal sentencing law, indicating that it may bar the use of acquitted conduct at sentencing where defendants have been acquitted of some charges but convicted of others. This would represent a major change in federal sentencing law. Currently, federal judges may sentence criminal defendants based on conduct for which the jury acquitted them. This is an incredibly unfair practice as it means that a defendant may go to trial on two charges, get acquitted by the jury of the more serious charge when the jury finds that the government could not prove the offense beyond a reasonable doubt, and then still be sentenced as if they had been convicted of the more serious charge.

Acquitted conduct is an offense for which the defendant was not convicted. For example, in many cases, defendant could be charged with guns and drugs at the same time. The penalties for federal drug offenses can be draconian on their own, but the presence or use of a firearm during the commission of the drug offense can result in mandatory minimums and federal sentencing guidelines that are exponentially higher. Federal judges take the guidelines incredibly seriously, so the guideline calculation is extremely important. Currently, there is nothing preventing federal judges from treating a defendant who has been convicted of a drug offense but acquitted of the firearm offense the same at sentencing as if the defendant had been convicted of both offenses. This can lead to a drastically longer sentence even though the jury partially acquitted. Federal judges also may often consider conduct for which the defendant was never charged.

Similar sentencing issues can arise in white collar cases, as well. For example, where a jury acquits a defendant of some counts related to a fraud scheme but convicts on others, the judge can currently sentence based on dollar amounts involved in the counts for which the defendant was acquitted. Because the loss amount involved is often the most important factor in the federal sentencing guideline calculation, this can have a significant impact on the resulting sentence.

Numerous defendants have attempted to challenge this practice as violating the Constitution in the United States Supreme Court, but the Supreme Court has rejected those challenges. The Supreme Court concluded in United States v. Watts that “a jury's verdict of acquittal does not prevent the sentencing court from considering conduct underlying the acquitted charge.” Some of the recently confirmed justices have previously signaled that they may reconsider that ruling, but so far, the Court has not accepted any petitions for certiorari on the issue.

The Sentencing Commission, however, could avoid the need for court action should it approve the proposed change. The proposed change would preclude courts from being able to consider acquitted conduct at sentenicng. The Sentencing Commission was created by Congress for the purpose of establishing the rules by which the guidelines are calculated. Ultimately, the guidelines produce a recommended sentencing range for the judge to consider when imposing sentencing. Until recently, the guideline range was actually mandatory and a judge could not sentence below the guidelines under most circumstances. The guidelines are no longer mandatory, but they are still extremely important.

The downside of the change being approved by the Sentencing Commission rather than the Court is that the change would almost certainly not be retroactive. However, this is an important change that strengthens the presumption of innocence and holds the government to its burden of proving a defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Criminal defendants should not be sentenced for things that the jury found that they did not do.

This change would only affect federal sentencing proceedings. It would not alter the current practice in the Pennsylvania state courts. The Pennsylvania state courts also use sentencing guidelines, but the guidelines are not quite as important as they are in federal court. The state courts are far more likely to depart from them. Further, it is relatively rare for courts to consider acquitted conduct or conduct for which a defendant was not charged in a state court sentencing proceeding. It is not necessarily prohibited at all times, but state court judges almost always agree that they should not hold alleged offenses for which a defendant was acquitted against them.

Facing criminal charges? We can help.

Federal Criminal Defense Lawyer Zak T. Goldstein, Esquire, at oral argument

If you are facing criminal charges or under investigation by the police, we can help. We have successfully defended thousands of clients against criminal charges in courts throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey. We have successfully obtained full acquittals in cases involving charges such as Conspiracy, Aggravated Assault, Rape, and Murder. We have also won criminal appeals and PCRAs in state and federal court. Our award-winning Philadelphia criminal defense lawyers offer a free criminal defense strategy session to any potential client. Call 267-225-2545 to speak with an experienced and understanding defense attorney today.